With the Cuban National Bank and the Cuban State now facing trial in London, an idea has recently been floating around in public debate: the “dictatorship’s” debts shouldn’t be paid.”

This has been a widely held opinion throughout modern-day history and it’s based on the fact that when there’s a change of government, winning forces tend not to recognize the validity of legal transactions carried out by previous administrations.

However, this argument has failed to stand up on different occasions.

States have the sovereign right to decide if they pay back their debts to foreign creditors or not. But this choice bears consequences. If a State doesn’t meet their debt repayments with foreign lenders, this means that their access to international financial markets – which is needed to put development projects into motion that the national economy is unable to cover – can be blocked.

Foreign investors and financial institutions don’t hold a favorable opinion about countries that are trying to sidestep their debt repayments, even if it was a different government to the one currently in power that fails to meet these debt obligations.

In the creditors’ eyes, the State takes on the commitment to repay the debt, regardless of the Government who authorized the debt acquisition. A State’s existence does not depend on a specific Government, but on its worldwide recognition and the control it holds over a certain land and people, as well as other factors.

A change in a State’s political system doesn’t mean that the State changes.

States that undergo a change in political regime and hold a low international credit rating because of former governments’ actions, need to find some kind of solution with all of their creditors before they are able to rejoin the global financial market.

There are many examples to support this thesis. Here are some of the most relevant cases for Cubans, as they explain what happened during the transition of power from a totalitarian regime that decided not to pay the foreign debt previous Governments acquired.

GERMANY

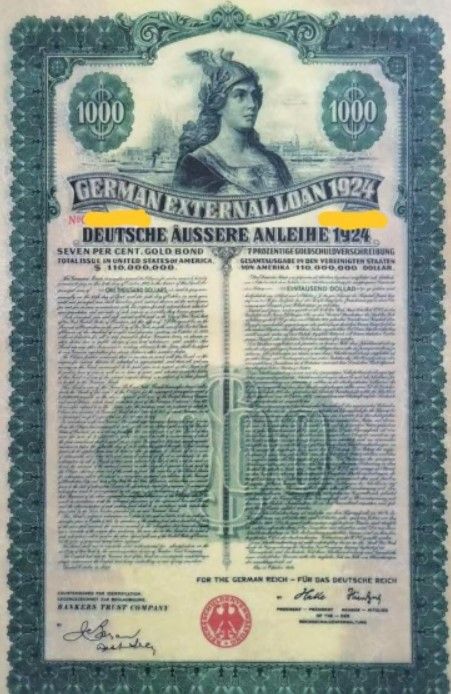

Foreign debt in lots of countries is broken down into bonds. Bonds are debt instruments issued by a State to raise funds. In doing so, it promises to return the bond’s par value back to the owner, as well as fixed interest known as a bond coupon.

In 1930, Germany issued a group of bonds (known as Young Bonds), as part of the Young Plan, that covered loans made by foreign creditors to boost recovery in the country after the end of the First World War. After Adolf Hitler’s rise to power (1933), the National Socialism Party’s Government decided to stop paying its bonds and called them “illegitimate”.

Yet, bonds “that were mostly issued in the form of a document at that time”, are instruments that can be traded. That is to say, owners can sell them to third parties, for a lot less than par value a lot of the time.

That’s what happened to Germany’s debt when Hitler stopped paying it. There were investors who bet that Germany would return to the global financial markets at some point, and when it did, it would have to find a solution to the foreign debt it had stopped paying.

This is what Andre Kostolany did, an Austrian-Hungarian who bet on accummulating this kind of debt bond when nobody thought the Young Bonds would ever be repaid and began to get rid of them. He took advantage of the situation and bought a large number of bonds for a lot less than their face value.

In the early 1950s, once the Second World War had come to an end and Hitler and nationalist socialism were defeated, Germany began to show signs that it wanted to restructure its debt and rejoin the global financial market. In order to do that, it had to reach an agreement with its foreign creditors in 1953.

The fact that Germany gave signs again of meeting its foreign debt repayments as a requirement to access new credit, meant that the Young Bonds also went up in value. Kostolany took advantage of the situation to sell the Young Bonds he’d collected for a low price and sell them for a profit. It’s calculated that in less than five years he made 139 times the money he’d invested on Germany’s defaulted debt.

In the 1970s, West Germany had paid off almost all of its debt linked to the Young Bonds. However, after reunification, it also had to accept the renegotiation of East Germany’s foreign debt, which had functioned completely differently and against West Germany’s model of State and government for over 40 years.

RUSSIA

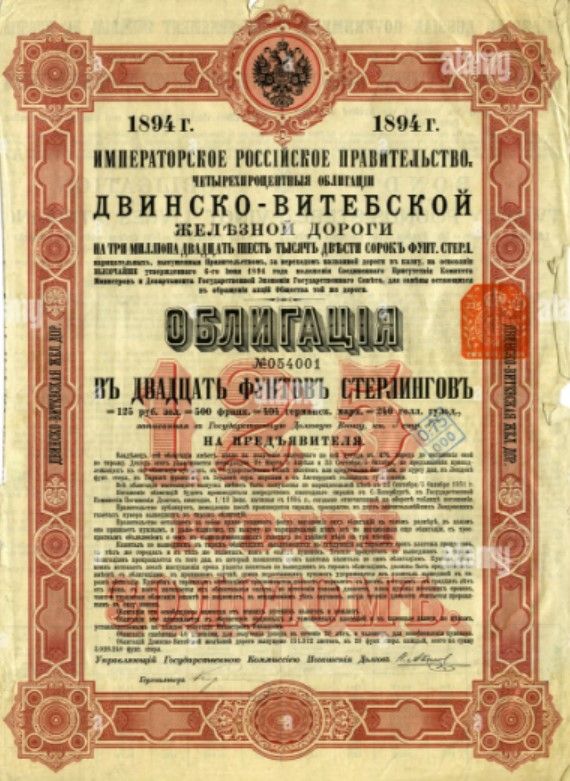

In the ‘80s, Kostolany invested in defaulted bonds again when nobody thought they’d ever be paid off: bonds issued during Russia’s tsarist era.

After the 1917 October Revolution, the Bolsheviks decided to stop paying the bonds issued by the Tsarist empire. At that time, the new Soviet Government declared the bonds invalid because they had been issued by an “illegitimate” Administration.

Despite repayments not being made, Tsarist bonds continued to be listed on the Paris Stock Exchange, and Kostolany invested 40,000 Deutsche Marks and bought a large quantity for just 1% of their face value (five French Franks each).

Just like Kostolany had hoped, the Soviet Union (USSR) collapsed, and Russia inherited the Bloc’s foreign debt and it not only had to renegotiate the late Soviet debt to rejoin the global financial market, but also the Tsarist debt.

In the mid-nineties, and as part of the foreign debt restructuring which Russia began after the USSR collapsed, the Russian Government reached an agreement with the creditors of Tsarist bonds. This agreement involved Russia promising to pay back 100% of the face value on every one of the tsarist bonds that were in the hands of European creditors. Once again, Kostolany made 100 times the value of the money he originally invested.

Furthermore, Russia renegotiated the Soviet debt with three groups of creditors: the countries grouped under the Paris Club (which accounted for almost half of the debt); commercial banks (that formed the London Club, with a third of its foreign debt); and the Tokyo Club.

CUBA

In the early ‘60s, Cuba’s “revolutionary Government” led by Fidel Castro also failed to recognize the foreign debt previous Administrations had raked up, considering them “illegitimate”. This went hand-in-hand with the expropriation of foreign companies, with compensation still subject of lawsuits today, especially those with links to US capital.

Over the following decades, the Communist Party’s Government accumulated a new several billion-dollar debt that it also stopped paying after 1986, and it negotiated a large sum of it after 2011.

History has shown that both the Cuban debt which Fidel Castro called “illegitimate”, as well as the debt that can go into default and be activated at the time the Cuban socialist Government disappears or changes, will need to be renegotiated by the new Cuban government. This will be an inexcusable requirement for the country to be able to access new sources of much-needed funding to rebuild the country.

Part of the current Cuban Government’s debt that it has refused to renegotiate was acquired during the Republic era and from expropriations under Castro in the early years of the Revolution. As well as its debt with the London Club, which figures in billions of dollars.

One of the creditors belonging to the London Club, CRF I Limited, which owns 1.4 billion USD in Cuban debt, is currently suing Cuba in a London court. A lawsuit where the Cuban Government’s defense has defended the unoriginal idea that the creditor isn’t “legitimate”.

However, despite its efforts, reality has proved that appeals about creditors’ or a debt’s “illegitimacy” are not enough to beat the reality of the market. A market that isn’t fair, but understands that the Cuban nation and State will always be responsible for any foreign debt any of its “Governments” take on.

In light of the situation today, one conclusion is crystal clear: the main struggle isn’t with creditors or speculators, but with the Cuban Government which continues to ask for money without producing, while it uses violence to stop the Cuban people from asking questions. However, the people will definitely pay for the government’s mistakes.

This article was translated into English from the original in Spanish.

Comments

We moderate comments on this site. If you want to know more details, read our Privacy Policy

Your email address will not be published. Mandatory fields are marked with *

dmott