The first thing that grabs your attention when you enter the coastal town of La Coloma, 26 kms away from the city of Pinar del Rio, is a giant lobster that welcomes you with open claws. My conversation with William [1] begins with a joke about this symbol. William has been living in this town for over 40 years, and is related – by family members, friends and acquaintances – with fishery work, which is the popular name for the La Coloma Fishing Industry Company (EPICOL).

“The only lobster we have here is the sculpture on the highway. It’s pretty much a ghost sculpture, because this animal isn’t meant for the Cuban people. It’s a “special” species, which is allegedly for the country’s economic progress, but not for its people. This is the harsh truth, which anyone in La Coloma can tell you,” William says.

What about the people who catch it? Can’t they even eat it? I ask. Not even lobster boat owners and their crews can eat lobster out on the high sea, the interviewee replies. He follows this up and tells me that everything that is caught needs to be handed over to ACOPIO (Cuba’s State purchasing entity) centers in offshore waters, near the cays.

“These are installations with docks and compartments, with large tanks in the water, where lobsters are separated by weight and measurement and thrown in. Every boat “kills” the catch of the day there, before nightfall. No boat can spend the night with lobsters onboard, under any circumstance. Using necessary fishing techniques – with large cages normally or a liftable fish aggregating device (FAD)-, they catch lobster, take them to the ACOPIO center, weigh them, hand them over, get their daily wage and leave. Boats leave the fishery regularly taking everything that is at these storage centers.”

The local man continues, “Once at the fishery, the transport boat enters through a place which is off-limits to fishing boats. It’s a closed and protected space where the lobster is unloaded and then processed or stored alive. There are security cameras within the processing plant, and at every entrance, to make sure that no animal “escapes”.

The La Coloma Fishing Industry Company is the leader in Cuban lobster production and “is responsible for over 30% of the Food Industry Business Group’s exports,” the local weekly newspaper Guerrillero reported on February 21st. In March 2019, Granma stated that the country receives 63 million USD per year just from lobster and shrimp exports. An article written by Cuban scientists, which was published in 2018, differs quite a bit though when it comes to this figure, stating that exports of spiny lobster (Panulirus argus) alone bring in close to 70 million USD in revenue per year.

With a university degree and masters in his field, my interviewee says it hurts sometimes to “think too much”. “Yeh, man, because if you think too much, there are things you just can’t explain,” he says with irony. “How can a people like ours, with a fishery that is processing dozens of tons of lobster every day, not be able to eat lobster without being scared? If it’s true that everything is being sold for the population’s wellbeing, why isn’t there a tractor to collect garbage? Why don’t polyclinics have ambulances a lot of the time?

“But people eat it, don’t they?”

“Of course they do, and they sell it, but ‘illegally’.” Depending on the season, you can find a packet on the black market for 20-30 pesos per pound. That is to say, a plastic bag with 10, 15 or 20 medium-size lobster tails can cost you between 150-300 CUP (6-12 USD), roughly.”

Recently, four illegal fishermen from Matanzas were caught by the Cuban Coast Guard, east of Isla de Juventud, with 20 sacks of lobster tails and meat (1.5 tons), according to the local weekly paper Victoria.

The interviewee says that law-breakers normally fabricate cages themselves with bunches of guano palm fronds and other materials, and then place them not too far from the shore in sea beds that are far from commercial fishing areas, and that’s where they do their business. The sad thing about this, from a biological standpoint, is that the lobsters they end up catching aren’t normally old enough or big enough to be caught.

“But if they catch you red-handed, you don’t only have to pay really expensive fines, but you get taken to trial for illegal economic activity, and go to prison. Over the years, there have been stories of fishery workers who have been caught with two lobster tails, and they’ve been fired without a second thought. Entire crews of a ship have been sanctioned and some have even gone to prison for selling lobster to the black market.”

I ask about lobster crew wages, who end up spending 20 of the 30 days in a month, out at high sea. William explains that wages depend on what they catch, on how many tons they deliver. During a regular season, this can be somewhere between 150-300 CUC plus 2000-3000 CUP per month, per worker. (230–420 USD)

“That’s a lot more than what any average Cuban worker earns.”

“Yes, but over the four months of the closed season (March-June), fishermen don’t earn anything, it’s like the idle period in the sugar harvest.”

Nobody touch anything…

It was the night of May 13th 1985. In his study at the Palacio de la Revolucion, in Havana, president Fidel Castro was talking to a group of Brazilians, including theologist and writer Frei Betto and his parents. Betto tells us: “My mother praised Cuban cuisine, especially the seafood. The cook, who was Fidel himself, agrees: ‘It’s best not to boil shrimp or lobster, as the steam reduces its substance and taste and makes the meat a little tougher. I prefer to bake them in the oven, or on the barbecue. You only need five minutes for shrimp on the barbecue. Eleven minutes for lobster if it’s in the oven, six minutes if it’s on the barbecue. I only use butter, garlic and lemon to season it. Good food is simple food.” [2]

The only conflicting detail about this scene is that simple cuisine isn’t legal for the first secretary of the Cuban Communist Party’s fellow countrymen.

Decree-Law # 103 Regulations for non-commercial fishing in 1982, signed by the then-minister of Fishing Industries and countersigned by Fidel himself, banned the “capture, unloading and transport, as well as the consumption or posession on board ships or by fishermen that practice recreational fishing” of “lobster, shrimp, prawns, and stone crab” as well as a limited number of other species. Anyone who does this, could be fined with an administrative fine of between 50-100 pesos.

Over time, the legal cost for fishing or trafficking the spiny Queen of the Caribbean, increased. Decree-Law # 164, Fishing Regulations, in 1996, remanded anyone who “catches, unloads or sells” “lobster, prawns, or stone crab”, and could be given a fine anywhere between “500-5000 pesos.”

Twenty-four years later, in Decree-Law # 1 Regulation of Law 129: Fishing Laws, published on February 7th 2020, not only was the ban ratified, but it was given wider scope. Now, anyone who dares to “catch, fish, unload, transport, process or sell, without due authorization […] species exclusively destined for state commercial fishing, starting with lobster, will incur a fine of a single amount: 5000 pesos.

With the peculiarity that “given the importance and severity of the violation detected, additional measures can be applied such as the obligation of […] suspending or revoking a person’s license, or not, and seizure of the product, fishing equipment and gear, including boats and naval devices, as well as any other means used to commit the violation or directly linked to this.”

Downhill for different factors

According to the FAO, in the 1978-1989 period, Cuba recorded an average annual capture of crustacea: 11,565 tons. This has waned significantly over following decades. Researcher Ofelia Morales Fadragas points out in her master’s thesis that between 2000 and 2009, the country recorded an average of 6000 tons; meanwhile figures from the Cuban National Office of Statistics and Information (ONEI) indicate that the average was 4391.4 tons, over the 2013-2018 period.

Several studies and press reports have pointed out the proper management of lobster fishing by Cuban authorities, with a closed season period for reproduction and to increase the minimum size of every specimen captured, among other advantages.

Nevertheless, we can’t disregard human actions, both on the island as well as in the rest of the Caribbean, as a key factor for this decline. The development of settlements in coastal areas, with all of the consequences this brings, is a heated debate on an international level. Plus, changes in temperature and the growing impact of hurricanes.

In the case of lobster, “we hope that it rests and regenerates; […] we are talking about 50 years of taking advantage in the wrong way,” El Salvador’s Mario Gonzalez, the director of the Central American Fisheries and Aquaculture Organization (OSPESCA), wrote.

“Basically, a fishery takes away the strongest individuals from a population. When a relatively long period of time passes, only the “strangest” genotypes remain: the less adaptable, the weakest, the ones that reproduce less… All of this negatively impacts the size of the following year’s population,” researcher Amilcar Mitjans Sanchez, from the Center of Fishing Research (CIP), told Progreso Semanal in 2018.

Anyhow, while biological reasons are used to justify the government’s zeal when it comes to catching lobster; the discrepancy lies in the fact that the thousands of tons that are being caught are “off-limits” for the majority of Cubans.

Options for the poor? Octopus tentacles, fishy water and tilapia

Months ago, some tins of “lobster soup” appeared on the Ideal supermarket’s network of stores in Pinar del Rio. They cost 6 pesos CUP (0.24 USD), and this already smelled “fishy”. It is nothing but the water that the crustacean is boiled in, seasoned with some seasoning and a tiny bit of tomato puree. The flavor kind of reminds you what the animal’s meat tastes like.

Less often, they also sell packets of rejos (head, tentacles and antennae) swimming in lots of tomato sauce for 15 pesos (0.60 USD). There is also the lobster option that the El Marino restaurant serves, the state-run restaurant with the longest-standing seafood tradition in the western province. I ask one of the sales assistants if they ever put lobster tails on the menu. She looks at me, rolls her eyes and “fries an egg” with indifference.

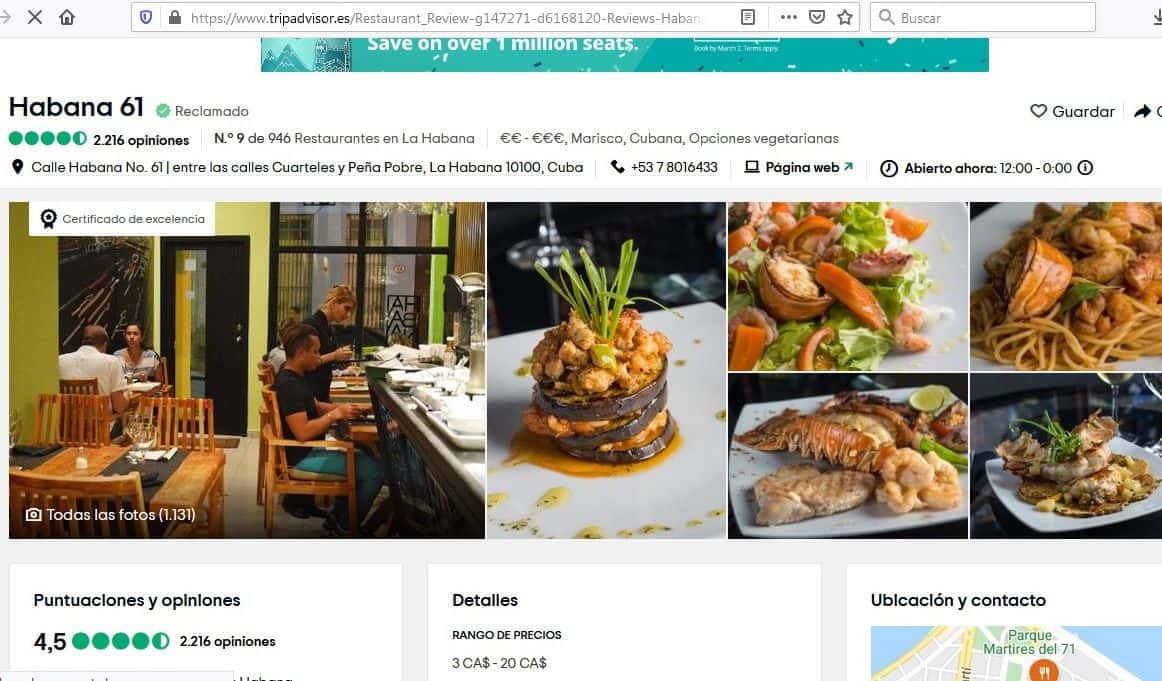

However, you just need to write “Cuban cuisine” or “Cuban restaurants” plus “seafood” in online search engines for promotions at luxury state-run and private restaurants to pop up, especially in Havana, with the forbidden animal on their menu. However, most of the time this option can cost more than 10 USD per meal, so your average citizen making 25-30 USD a month can’t even dream of it.

So, what can ordinary Cubans do to eat lobster? A note published in La Demajagua weekly paper, which was then proudly reprinted by the Granma website, points out a possible response, without even meaning to:

“As outlined by the president of the Cuban Republic, Miguel Diaz-Canel Bermudez’s guidelines, members of the seven Pescagram units, based in Manzanillo, encourage fresh water lobster and eel fishing for tourism and exports, increasing the number of tilapia and catfish for these markets and the domestic market, creating close ties with the University and improving technology.”

If this isn’t enough for you, reread a report from Trabajadores newspaper published in 2013 which concluded: “The black market is booming and is more than the effort of men such as Toti, Gervasio or Michel [lobster fishermen in Camaguey], who only know how to love and live off the sea, fishing a specimen that is highly lucrative the world over, which will be sold in international waters without ever reaching a Cuban table.”

—–

[1] The name has been changed at the interviewee’s request, to protect his identity.

[2] In his book “Fidel and Religion” (Oficina de Publicaciones del Consejo de Estado, Havana, 1985), pg. 35-36.

This article was translated to English from the original in Spanish.