t action has gone so far to the point that they find themselves prevented from signing a petition because of the possible reprisals they could face if they do so.

“We are students from the Department of Law at Havana University. A place we came, many years ago, with the dream of studying a prestigious degree. We came with the idea of doing Good for the People. That was before we discovered that there can’t be Justice where the Law is being prostituted. Now, we are disillusioned, half-way between our lives as students and an uncertain professional future.”

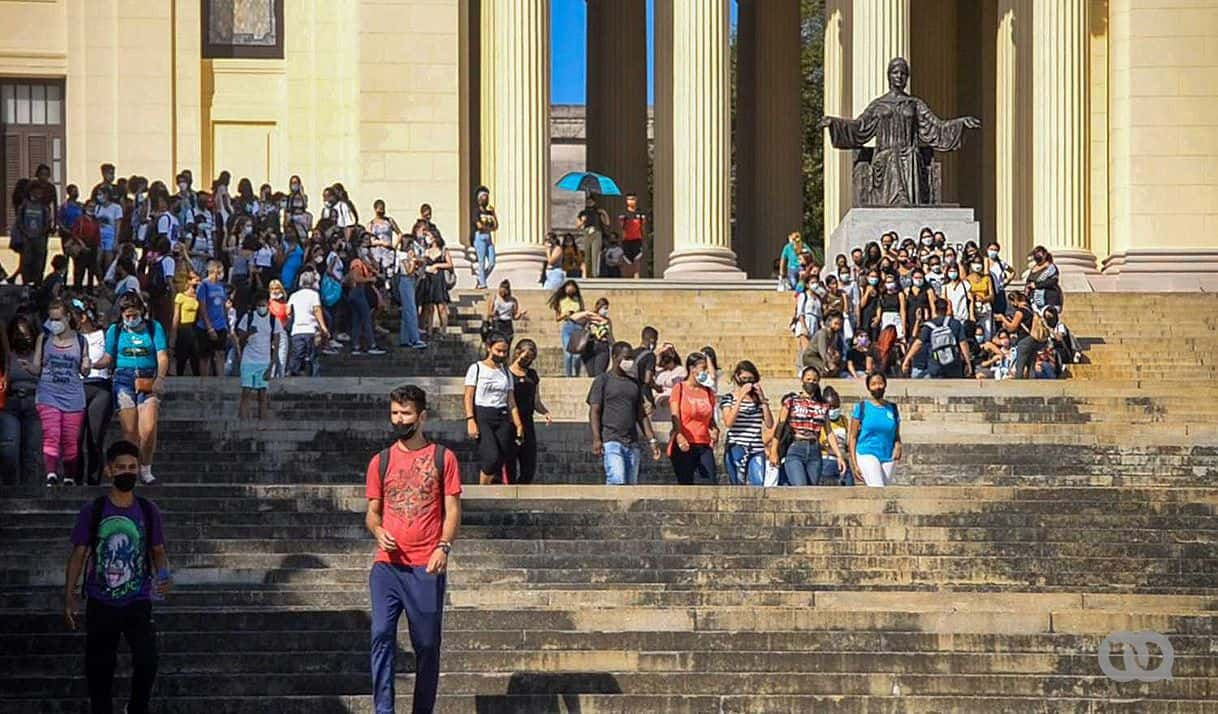

The sentiment expressed in this letter doesn’t only belong to these young people. Since 2021, Cuban students have written many statements to demand legitimate rights in the face of arrests and the unjustified expulsion of classmates and professors, or because they have been prevented access to studies in other cases, supposedly because of political and ideological differences with the Government in power in Cuba.

The letter from Law students states that they come from families who are committed to the Revolution, but that their parents are full of sadness, fear and disappointment. Today, they just want their children to take their degrees and go someplace else where they can live a decent life, without hardship and in freedom.

Their words are confirmed by the latest migration wave Cuba has seen – 300,000 Cubans arrived in the US in 2022 alone. The vast majority of emigres are less than 35 years old; some haven’t even finished their university degrees yet.

You don’t need statistics or numbers to confirm these Law students’ claims. You just need to look within Cuban families, or on social media, to see most Cubans’ apathy and disappointment.

Professors against students?

Very little or nothing is known about the ideological debates that surely take place in Cuban university classrooms. Even though news of students and professors being expelled or sanctioned for having “opposing views” is becoming more and more frequent and visible, many prefer to “stay within the box” to complete their degree, get their qualification and leave Cuba. In reports published by the state-controlled press, the phrases “committed youth”, “trust young people” and “we are continuity” are regularly repeated by student leaders.

However, some students do take to social media to report the injustices that are committed on a daily basis, linked to their future profession or not.

In the case of the Department of Law at Havana University, signatories of the letter complain about the hypocrisy of their teachers, their lack of ethics as teachers and lawyers and their lack of commitment to the truth; the privileges of opportunists; the imprisonment of hundreds of Cubans for protesting and demanding a better country; the approval of “a criminal Penal Act, which seems to be ripped out of Batista’s or Pinochet’s notebook,”; fines for posting critique of the Cuban Government on social media or for buying or selling goods that can’t be purchased in stores with a state wage.

“Our professors in the Department say nothing about any of this,” the statement continues. “Of course, they know what’s going on, they just lack dignity. But they are way too cynical and opportunistic. They spend all of their time chasing down positions, trips abroad and requests of the Government. We don’t talk about human rights in our classes, and when we do, it is spoken about negatively, in passing, as if they were something distant and abstract. Nor we do we talk about how in a country like ours we can have a democratic Constitution, but then civil rights are trampled all over at the same time. Why are we studying Law in these conditions?” the signatories ask themselves.

In the letter, the future lawyers mention professors and doctors in Legal Sciences Julio Fernandez Estrada and Rene Fidel Gonzalez, both of whom were dismissed from their positions because they were considered “problematic”.

In the case of Professor Rene Fidel Gonzalez, a statement from the University of Oriente (OU) admitted that he had been expelled because of his publications on websites such as La Joven Cuba, Cuba Posible, Rebelion and Sin Permiso, the latter two being reproduced and reviewed by the Cuban press when it suits them.

The UO statement recognized the influence Professor Gonzalez had on his students, who he “confused” with his way of thinking. The statement is contradictory in the fact that it says political discrimination and the expulsion of teachers from Cuban universities is an “error”, while all of the reasons laid out in the document to justify Rene Fidel’s expulsion are based on his critical publications and opinions.

In his case, it once again emerged that “university is only for revolutionaries,” a phrase that contradicts the alleged right every Cuban has to further education, without discrimination.

On the other hand, Professor Julio Antonio Fernandez Estrada found himself forced to leave Havana University after being persecuted by Department of Law leaders. Even though he then spent some years as a teacher of a municipal course for employees, his work contract as a teacher was later terminated there too. While he protested and wrote letters, the former dean of the Department of Law responded that the University didn’t have a problem with him, and that he wasn’t being hired because of an administrative decision.

“I’ve kept every letter, signature, receipt, from all of these years, including the letter in which my father, a renowned professor at UH, hands in his resignation. Eight years later, another professor from the Department handed in his resignation in protest of the termination of my contract as a professor of distance learning classes, the only ones I’d kept doing since 2008.

“I talk to the army of professors without work because of injustices committed in the workplace, administrative processes of political censorship. I’m asking Cuba’s citizens to hear our complaint. We’ve endured this discrimination in silence, for years. It doesn’t matter if we’re Communists or Liberals, Socialists or fans of the free market. We’ve been denied our right to work as educators because some committee finds us inappropriate,” the lawyer insisted.

The Law students who openly published their letter recently say that they wrote the statement as a complaint, because they feel powerless given the impossibility of changing things from within the system. They say it hurts them to do this, referring to the establishment where they are studying and where they’ll receive their degree, “but we have to pay our own debt to the society that made us, by telling the truth.”

Julio Fernandez found himself forced to leave Cuba, while Professor Rene Fidel has presented several complaints to the Publi Prosecutor’s Office for years, because of violations of the Law in his case; however, he is still awaiting a response.

Expulsions, contract terminations or different conditions for professors critical of the government in Cuba today, have all become common practice. Other cases include that of Omara Ruiz Urquiola with the Superior Design Institute (ISDi) and her brother Ariel at the Department of Biology, Doctor Omar Everleny, who was expelled from the Center for Studies on the Cuban Economy; Professor Roberto Peralo, from the University of Matanzas; Jose Raul Gallego, a professor of Journalism at the University of Camaguey, who was expelled for collaborating with independent digital media platforms, and Dalila Rodriguez, professor at the Central University “Marta Abreu” of Las Villas, for “damaging students’ learning”, even though she didn’t belong to any political group.

The latest case was that of professor and journalist Jose Luis Tan Estrada, who was barred from teaching at the University of Camaguey because of his posts on social media.

Other student demands

In mid-2022, the young Catholic intellectual Leonardo Fernandez Otaño was refused a doctorate in Historic Sciences at UH.

Fernandez Otaño was imprioned for peacefully protesting on July 11, 2021. Then, in February 2022, he was informed that he had been excluded from the postgraduate program at UH – even though they’d told him otherwise. Justification for this decision? The academic didn’t have a professional connection, which prevented him from getting a doctorate, and the tutor who would oversee his thesis had withdrawn. Both arguments were debunked by the historian himself.

“(…) State Security and its branches within Cuban Academia, which should be called upon to respect diversity of opinion because of their respect for social and human sciences, have deployed a series of actions to ban my presence in a place of postdoctoral studies, which I’d gotten into because of scientific merit and in accordance with civil rights,” Fernandez Otaño posted.

As a result, almost a hundred Cuban students and university graduates addressed an open letter to the Academic Committee of the Doctorate in Historic Sciences at the Department of Philosophy, History and Sociology at UH, in which they demanded transparency of procedures and in academic and administrative decisions.

The signatories urged them to review, duly analyze and rectify the decision to exclude Fernandez Otaño from the Doctorate Program he’d applied to, which the academic had a right to, in accordance with current legislation in Cuba.

“We demand that members and leaders of the institution in question publicly explain their reasons (with objective arguments) that led to this controversial and intransigent decision, thereby clearing any doubts about the hypothesis of this group’s involvement in the discrimination that Leonardo Manuel Fernandez Otaño has been continuously subjected to for political and ideological reasons,” the document pointed out.

Days later, academics and students complained that their letter hadn’t received a response from the recipient institution, which had remained indifferent without issuing an explanation or giving any kind of reaction. They added that the intransigent and unfounded decision to prevent Leonardo Fernandez from beginning the doctorate remained and, as a result, the signatories’ demand remains as well. Furthermore, a printed copy of the letter had been handed in to the Postgraduate Department at the Department of Philosophy, History and Sociology at UH.

After the 11J protests, another group of students, professors, gradates and ordinary citizens expressed their concern for the irregular situation of those under arrest. Taking Article 53 of the Cuban Constitution that legitimizes them as citizens to request and receive accurate, objective, and timely information from the State, they went to the Public Prosecutor’s Office and to its head, the Federal Public Prosecutor Yamila Peña Ojeda.

“Our concerns grew given the fact that the abovementioned prisoners included minors, who didn’t hold the minimum legal age to be criminally accused, in our understanding, which isn’t an insignificant point bearing in mind the attitude of law-enforcement agencies during police operations,” the signatories wrote.

In the document, they request the immediate release of students in prison, until they clearly explain the charges that led to their arrest; that trials against imprisoned civilians be made transparent immediately and information given to their families and public opinion without infringing on prisoners’ right to personal and family privacy, until an administrative or judicial resolution that resolves their legal situation once and for all is proclaimed.

They also urged that differential treatment be given to prisoners who are minors, that go beyond safeguards of criminal procedures outlined in the Law and protected by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which Cuba has signed and ratified, acting in the best interest of the child and providing them with psychological assistance, if they need it, to counteract the trauma caused by this whole situation.

The Facebook page Reclamo Universitario has collected several declarations from students after the mass protests on July 11, 2021. The profile description reads that it is “a space against hate and oppression, for community-led solidarity and social justice.”

One of the statements they posted mentions the complaint a group of university students made to the National Secretariate of the Federation of University Students (FEU), to the Secretariate of the FEU at UH and different departments, and to the Dean of UH, in the interest and defense of student Leonardo Romero after his arrest and imprisonment since April 30, 2021.

Students demanded the university organization intervene so that no reprisals would be taken against Romero at UH. Meanwhile, they asked the FEU to take a stand and intervene in the case something similar happens in the future. “A university student has the right to express themselves peacefully and publicly in the face of any situation that makes them uneasy, just like any other citizen,” the students pointed out.

Students complaints have also been seen outside Havana, although less frequently. In mid-2022, there was a student protest that went beyond statements and letters. Scholarship holders at the University of Camaguey’s Agramonte campus, led a protest where they shouted slogans in chorus to demand the electricity be switched back on after a blackout nearly 12 hours long.

While some professors tried to do “damage control” by saying that it hadn’t been a protest as such, videos on social media and some students’ statements proved their exhaustion and apathy towards a reality that not only affects the academic year, but also their personal lives.

This article was translated into English from the original in Spanish.