Enshrouded in darkness, twenty-something people are waiting on the block of a store in the El Roble neighborhood, in Guanabacoa, Havana. Some are sitting on the curb. Others are sitting on pieces of cardboard laid out on the ground. They cover themselves with coats and quilts they’ve brought from home. Night becomes dawn and record low temperatures have been recorded in the Cuban West, over the past few days.

When morning finally breaks, the line to take numbered tickets, that will organize purchases of chicken that came into the store the day before, finally take shape. The group of 20 will soon become one of over 60. Every person spends the night taking place for three, four or even five more buyers. Some of these buyers are family members, neighbors or friends… other times, they’re for strangers who they will sell the place in line to.

Sitting on the cold concrete of the sidewalk, covered in blankets, Alicia grumbles under her breath: “There are people here who aren’t even supposed to be buying at this store. I’ve already gotten into arguments over this. If you belong to another bodega rations store, what are you doing here? Go hustle where you’re supposed to!”

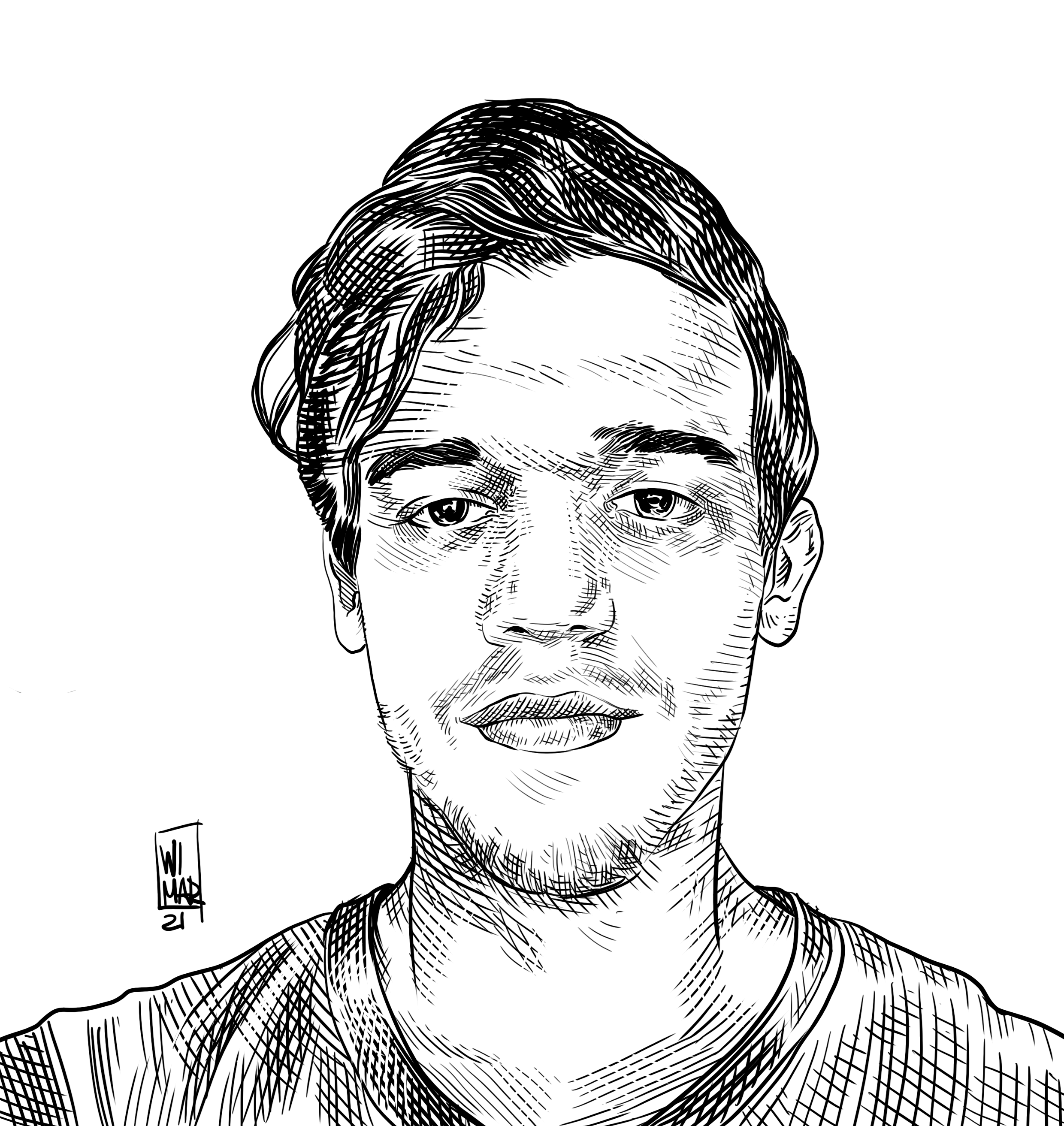

Alicia

Curled up in a ball on the ground amidst blankets, Alicia seems like an insignificant bundle with her head of fine and long hair, but once standing, she can look over almost anyone with her above-average height. Being tall also makes her look slim, and her tight-fitting trousers and blouse add to this effect.

Her slightly muscular but fibrous shoulders, abdomen and legs go back to a time when she tried to go to the gym and have the “perfect” male body, which ended in the Military Service, when she recognized herself as a transexual woman.

Alicia lives five blocks away from the store, on the third floor of what has become a small family building, after being her grandmother’s relatively spacious home. Over time, it took on a second floor, where her mother’s tighter home was built, and then a third floor which is now hers: a rough room, with bare-bricked walls and tarpaulin hung up to cover the holes where two unfinished walls stand.

It’s almost 3 PM and Alicia begins to get ready for her night-time task. She takes a small drawstring bag and puts a bottle of water and a plastic container with some food in it. A bit of rice, tomato slices and some pieces of chicken should be enough to keep her going until tomorrow.

She puts her cellphone on charge. She sits on an iron chair to rest a little. She crosses one leg over the other and rests her hands on her knee. Her long and perfectly-manicured pink nails contrast with the premature wearing away of her 23-year-old’s teeth.

“I’m unemployed, so I have to hustle to earn money,” she says with a half-smile that suggests more pride than sadness.

She studied up until nineth grade; then she went to a technical school which she went to “so much” that she can’t even remember what it was about now. After her Military Service, she tried out Havana’s night-life for an elusive period of time, which she doesn’t really talk about, and she contracted HIV. She displayed a slight interest in hairdressing but it never went anywhere and, now, she gets by in lines and thanks to selling the powdered milk she receives for her disease.

She started out in this line business when the COVID-19 pandemic came. She would go to the store in El Roble and the one in the nearby Chibas neighborhood, sometimes to El Triunfo, near Guanabacoa Park, or any other store where she knew something good was going to be sold; mainly chicken, detergent, cooking oil… Basic essentials.

She would buy them, keep some for herself and resell the rest. This gave her very little means but enough to get by, although she’d have to walk far away and spend sleepless nights. Just to get the basics for the house and also make an extra bit of cash.

Later on, the municipal Government imposed measures that stopped her from following her normal routine. Ever since then, you can only buy at the bodega store that is assigned to every registered consumer.

Plus, basic products are rationed. For example, in households of up to six people, you can only buy one 5 kg packet of chicken per month, two packets if there are 7-12 people and so on. In order to do this, you have to show your rations booklet at the store, where they make a note of this purchase so that this household of consumers are unable to buy the product before the allowed period of time.

“I can’t sell what I buy anymore, because it’s not even enough for me. We have two rations booklets in our house: one for my grandmother and two uncles, and the other one for my mother, her husband and me, and I also live with my partner. How’s one packet of chicken a month going to be enough?

Anyway, she picks up her backpack, folds two blankets that she keeps in a cloth bag and heads for the store. Even though she needs to hold onto what she buys to get by, an opportunity to make a bit of cash always presents itself once in line.

The line

There were several state-controlled retail points in El Roble: two TRD kiosks that no longer exist; a CUPET gas station that was half-destroyed by a tornado in 2019 and is an abandoned ruin today, covered in foliage; and the store where people line up now.

The store is in a place marked out by a block of stonework with a thick nameplate that was made about five years ago. The windows used to open out to the street, but they were barred up. When it’s hot, which is the most part of the year, staying inside is smothering.

Around 4 PM, the last sales of the day are still being made. There are very few people left to buy. However, another line begins to form and grow on the corner.

Alicia greets the people she knows. She asks who’s last in line. She leaves her backpack and quilts on the ground and sits on a bit of the broken sidewalk, under the shade of a tree. It’s best not to tire yourself out too early. It’s going to be a long wait.

The line that’s forming in the middle of the afternoon is to buy tomorrow. It’s like this every day. Only the number of people varies depending on the product the store has or they know is going to come in early the next day. You almost always know what’s going to come in, somehow.

There are people wearing shorts, flip-flops and a t-shirt… Afternoons aren’t chilly, but the night is expected to be cold, so others come already wearing trousers and a jacket tied around their waist.

“Who’s last?” a new-arrival shouts.

“I am,” Alicia replies. “And I’m with four other people,” she warns him.

Then she explains, in a whisper:

“Everyone nowadays takes a place for four or five people. You can’t say ten though, because nobody will let you; but if people say, for example: “I’m with four and I’m behind somebody who isn’t here right now, but they are also coming with four people.” It’s a lie, a hustle, but you have nine turns plus your own. People begin to come in the morning, before they hand out tickets, and somebody will buy those turns off you.

“It was cheaper before, but right now you can’t get a place in line for less than 100 pesos. If it’s chicken in the store, for example, or something that’s really hard to find, you can sell each place in line for 150-200 pesos.”

Alicia isn’t the only person from her block here. Her next-door neighbors are also in on this “business”. They are an old woman over 70 years old, her 50-something year old daughter and her two children. As there are lots of them, they normally end up making more than those who come alone.

In addition to selling turns, they have collected a few rations booklets. They can each buy with two. The real owners of the booklets give them to them so they can buy, and then they pay the person who waits in line or split the products in half.

This family always has something to resell. Alicia complains that the last time they offered her two packets of minced meat, which costs just over 30 pesos at the store, but they were selling it for 120 pesos each, which was supposedly a preferential rate for her as she’s their neighbor. They sell packets of chicken for 400 pesos, almost double the state price.

Around the corner from the store, there’s a huge building that used to be a factory and was converted into a homeless shelter few years ago. Some forty families must live there. They call it “el Quilombo” and some of its inhabitants also form part of the neighborhood’s “line elite”. They move around as a group, have a representative in every line and normally get the first turns.

The line has its leaders, its typical figures, it’s own rules for working that only those inside its inner dynamic understand, out of practice and training. It’s a system where the simple buyer is the last link in a food chain that can’t be seen in plain sight. Alicia would be a tiny businesswoman swimming amongst the big fish, but she always manages to take a piece of the “banquet”.

The night

Not everybody stays once the sun sets. Some people normally go home and leave a neighbor or family member looking after their place throughout the night. There are neighborhoods where a more or less organized system has been articulated where a different person has to stay every time.

If you’re coming alone, then you’re pretty much forced to stay the entire night with those who take the night in shifts, who never leave their place. Thus, the line becomes a strange combination of a boring campsite and a street party.

Some people sit on the ground, scrolling on their cellphone or catching a bit of shut-eye here and there. People who live nearby bring chairs or stools from home to try and be a little more comfortable. A winter gust of wind freezes my face and brings the smell of burnt tobacco towards me, which penetrates the thin fabric of my mask and fills my lungs.

Isolated sighs and cellphone notifications are the background noise to the raucous conversation between a group of woman from el Quilombo and Alicia and her neighbors. They get on well. Despite being commercial rivals, somewhat, they understand that there’s loot for them all and they make a good relationship their priority.

Everyone’s eaten something by then, whether it’s from a container they’ve brought from home or because they quickly went home for a couple of minutes and came back. The women from el Quilombo make the most of the night: they’ve brought two bottles of rum to share. They open the first one. They spill a bit onto the ground for the saints. The smell of recently-opened alcohol mixes with the smell of cigarettes and damp grass with dew beginning to form.

The women from el Quilombo, Alicia, her neighbors and a few other guests take their masks off down to their necks, they drink from the same cup, they talk, they have fun… Until early morning draws near and sleep weighs heavy on their eyelids.

A patrol car passes by two or three times during the night, at least. When they hear the tires scratching the asphalt and the white car appears from out of the darkness, the alcohol disappears, the masks go back up and, those that aren’t sleeping, keep quiet and stay alert. Only the cicadas dare to hiss on top of the vehicle’s engine, that goes slowly, like a nocturnal creature watching over its territory, with everyone watching it, until it turns the corner and disappears.

This has become a normal routine now, but Alicia remembers what it was like before, when the pandemic was at its peak, and how things were really “fun”.

There was a curfew from 9 PM until 5 AM and, if they caught anyone on the street during that time, they would be fined up to 2000 pesos.

People waited in line in every possible way “and with more determination”, because of the risk and adrenaline involved. You had to sit in doorways or corridors near the store, look for the darkest place possible and stay still for as long as possible.

Sometimes, people would hide in really obvious places, the patrol car would pass by with its headlights on and then there would be a chase. Neighbors who also heard people moving around would come out shouting or call the police. Others charged people to spend the night in their doorway or garage. 50 pesos per person.

Alicia ended up down at the police station one of those nights. There wasn’t a curfew anymore, and despite having her reflexes from that time, she was standing, talking, and didn’t hear the patrol car coming. When she heard it, it was almost on top of her. She instinctively began to run to hide. One of the police officers got out of the car and chased her; the other one followed her in the car. They trapped her. They took her down to the station. There, she found out that somebody had tried to rob a home near the store and that her weight and height matched the suspect’s description. She spent the night in a cell.

“Now they pass by, they see you and they don’t do anything,” she says, strangely disappointed.

Selling

People begin to come at around 5 AM asking who’s last in line, but it isn’t until the sun comes up, just after 6 AM, that most people show up. New people, the people who left somebody looking after their place and come back, friends that somebody brought and cut in… In a matter of minutes, there are over 100 people in line. Anyone coming from now on runs the serious risk of not being able to buy anything until the next day.

That’s when the line-sitters begin to work, carefully, because they can’t “give out and shout that they are selling places.” According to their code, you go up to somebody you know: “Hey, I have a place, you want it?,” then you go up to someone else, and so on.

A woman greets one of Alicia’s neighbors and asks her for a place directly. There are people who know them and don’t beat around the bush. The line is “full”, but that’s not a problem, she calls one of the women from el Quilombo and gets her a place immediately. Maybe she takes a cut.

The organizers arrive and ask for order so they can give out the tickets.

The line, this scattered animal in the night, begins to take shape in the day. Standing one behind the other, the line unexpectedly gets longer. It takes up the whole block, goes around the corner and down the hill of uneven pavement.

Alicia has been able to sell three places. She has two left because she still can’t buy chicken, so she can also sell her place. She gets in line, hoping that last-minute buyers show up.

Nobody comes. She could take the number and then try and give it to somebody, but she’d have to spend longer in the line and she’s tired. She leaves the group and walks away, happy with her 400-something pesos.

She’ll go to sleep now and in the afternoon, she’ll come back to work if she feels up to it. If she doesn’t, she’ll come tomorrow. At the end of the day, lines are never-ending.

This article was translated into English from the original in Spanish.