Confronting Power, 11J and What Happened the Day After

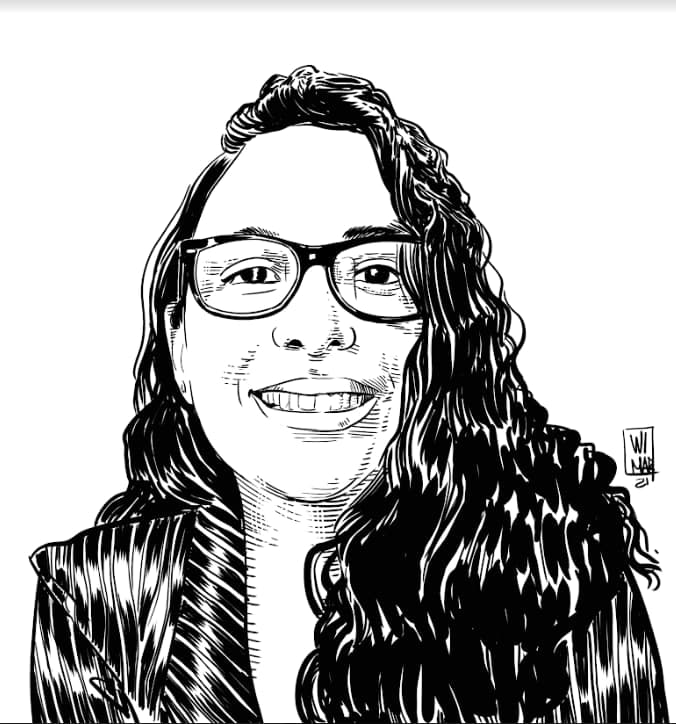

Protests on July 11, 2021 in Havana. Photo: elTOQUE.

Cuban civil society’s vulnerability and the unexpected protests on July 11, 2021, didn’t stop the civil movement the day after. Contrary to what might happen in similar situations, various initiatives were started up – both inside and outside the island – wanting to be useful somehow. Initiatives that initially completely focused on discovering the whereabouts of detainees and the disappeared.

What started out as a list – which was first brought to light with posts and reports on the Facebook page DESAPARECIDOS#SOSCUBA – written out in an Excel sheet, which several women (both inside and outside Cuba) used to compile information – taken from public complaints and direct communication with family and friends of protestors, which then became Justicia 11J.

Today, Justicia 11J is a working group about politically motivated arrests in Cuba. It was founded by Camila Rodriguez, Cynthia de la Cantera, Darcy Borrero, Eilyn Lombard, Ivette Leyva, Laritza Diversent, Kirenia Yalit Nuñez, Maria Matienzo and Salome Garcia.

The dimension and scope of these women’s work, over the last year, has been crucial, especially in three basic aspects. First of all, by constantly reporting the violations committed against protestors – from their arrest to every phase of their criminal trial. Secondly, by giving great visibility to the issue on an international level and campaigns to release incarcerated minors. Last of all, by giving support, following up with and helping protestors’ families.

Thanks to Justicia 11J, in the early hours after July 11th, we already knew who some of the detainees and missing persons were, and this gave a numerical idea – albeit a rough number – and human aspect to the repression unleashed by government forces after Cuban president, Miguel Diaz-Canel, gave the combat order.

Thanks to Justicia 11J, there is an exhaustive statistical record – that was improved as days passed by; it is a document and archive that is historical in nature. Today, this record allows you to not only consult the name of the people who were and are victims of State punishment, but also other important variables when it comes to analyzing and studying what happened – age, province and place of imprisonment, gender, ethnicity, profession, assurance, sentences, prison facilities and photos of the accused.

Thanks to Justicia 11J, we now have an independent tool – free from government pressure or cover-ups – that, despite being under-reported, has revealed discrepancies within the official version. Discrepancies which, in some cases, have exposed the selectivity of public information from institutions; while, they’ve shown the greater dimension of punishment.

On July 18, 2021, seven days after the protests, the Cuban Conference of Religious Men and Women (CONCUR) announced a service to follow-up on 11J detainees and their relatives. The service focusses on three aspects: advice for presenting habeas corpus documents, helping to locate the whereabouts of the detained, and spiritual and psychological support.

Organizations such as the Cuban Observatory of Human Rights and Prisoners Defenders have also helped to contribute and disseminate records of the detained and missing persons after 11J. Furthermore, Prisoners Defenders presented a complaint to the UN Committee of Enforced Disappearances, on July 14, 2021. The appeal managed to get the UN to demand urgent information from the Cuban Government to reveal the whereabouts of incarcerated protestors.

Students, professors and graduates from Havana University delivered a letter to the Ministry of Higher Education (MES) headquarters to demand the immediate release of arrested students. The letter was addressed to the MES minister, Jose Ramon Saborido, who they demanded intervene immediately because this is a violation of students’ rights. The document also demanded the MES take a public stance on the events and to follow the trial hearings of students.

Meanwhile, students from the Art University’s Faculty of Audiovisual Communication (FAMCA), came forward in favor of the protest, and against the call for violence and the slander campaign of the protests in official media. The Biology Department at Havana University also joined in on similar complaints; such as support and follow-up service for victims of gender-based violence YoSiTeCreo in Cuba.

Despite the disbandment of a project as well received as Archipielago – especially after the unexpected departure of its main organizer, Yunior Garcia Aguilera – the citizen-led platform managed to establish itself as a solid movement. Even though it might be remembered for their call for a peaceful popular march on November 15, 2021, the main objective of Archipielago’s struggle was to release 11J political prisoners.

Other initiatives focused on raising money, collecting medicine, food, clothes and shoes for prisoners and their families. These include Te Presto Mi Voz, led by Luciana Covin – a Cuban living in Europe and a political prisoner’s granddaughter. The project existed before 11J and their objective was to find sponsors for Cuban prisoners, but after the social uprising they joined efforts to send a weekly bag – including medicine – to protestors who need them. On their Facebook page, they also follow court cases, sharing information about prisoners, as well as complaints from family and friends.

Some of the leading figures of Te Presto Mi Voz moved ahead with another project called La Jaba de los Inocentes (The Innocent’s Bag); with the mission of also getting food from outside Cuba for 11J prisoners.

The “Donde tú caes, yo te levanto” (Where you fall, I’ll lift you up) campaign, by the San Isidro Movement, mobilized after 11J. Coordinated by activist and art historian, Anamely Ramos, the project channeled its efforts on getting basic essentials to victims of repression during the protests, as well as serving as an intermediary with organizations offering legal counsel. They created an open WhatsApp group, called Botiquin MSI, to work out logistics.

Ayuda a los Valientes del 11J (Help to the brave of 11J) emerged in Santa Clara as an aid initiative to take food for prisoners in prisons. On the other hand, the group Cubanos Canadienses por una Cuba Democratica joined prisoners’ public complaints and made a relay of fasts to accompany the hunger strike held by Barbara Farrat Guillen, the mother of Jonathan Torres, who was released after almost a year in prison.

Many political prisoners’ mothers have also raised their voices and stood together in their demand for justice for their children. They have reported cases of abuse, violations of due process and arbitrary sentences, both individually and as a group. These mothers have sent a letter to President Miguel Diaz-Canel, which was delivered by Barbara Farrat and her husband to the State Council’s Citizen’s Assistance Office. The letter had over 150 signatures.

Mothers that have publicly complained about the situation of their incarcerated children include Barbara Farrat, Yanaisy Curbelo (Brandon David Becerra’s mother), Yudinela Castro (Rowland Castillo’s mother), Elizabeth Leon (Frandy Gonzalez Leon and Santiago Vazquez León’s mother), Migdalia Gutierrez (Brusnelvis Adrian Cabrera’s mother), Maria Luisa Fleitas (Rolando Vazquez Fleitas’ mother). Andy Garcia’s family have also been prominent, as well as the forceful voices of fathers like Wilber Aguilar (Walner Luis Alguilar’s father) and wives like Lazara Roblebo (Jose Antonio Gonzalez’s wife) and Saily Nuñez (Maikel Puig Bergolla’s wife).

On the other hand, GuajiroBot is a Twitter bot created by Danilo El Cubano, in April 2022, which “provides information about Cuba and its struggle for freedom.” How does this initiative work and what does it entail? If a user on this social network tweets “@guajirobot denuncia” (reports), a response automatically appears including a photo of a political prisoner and their personal information. Activists use it to respond to tweets by president Diaz Canel.

Other group actions – mobilized outside of Cuba – and appeals from international organizations have also contributed to the campaign complaining about the excessive force used by the Cuban Government against 11J protestors and seeking their release.

These include the joint statement made by over 300 figures from the art world – on December 8, 2021; the European Parliament resolution comdemning government repression – approved on September 16, 2021; the statement made by UN reporters at the High Commissioner for Human Rights Office on October 25, 2021; the appeal for freedom for Cuban political prisoners at the UN Human Rights Office in November 2021; and the statement from Josep Borrell, the EU High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, who urged the Cuban leadership to release political prisoners.

While it’s impossible to know which of these actions have influenced releases, few absolutions and changes to sentences of 11J protestors, and to what extent, it’s true that they have challenged and pinned the Government, and they still do. Legitimate protest and complaints in places like Cuba have become fundamental weapons against institutionalism that doesn’t respect justice.

Civil society is a vital part of society. Voluntary associations are the backbone and they don’t belong to the Government. According to political expert John Keane, voluntary associations are meant “to keep and redefine the borders between civil society and the State via two interdependent and simultaneous processes: the expansion of social equality and freedom, and the reorganization and democratization of the State.”

This article was translated into English from the original in Spanish.

Comments

We moderate comments on this site. If you want to know more details, read our Privacy Policy

Your email address will not be published. Mandatory fields are marked with *