Nine years after his time in Angola, Cuban doctor Emilio Arteaga still recalls it as the worst of the three international missions in which he had worked. He may have purposely blocked out most of his memories, as a «defense mechanism», but has not forgotten the feeling of suffocation, an irreparable loss, and the «militarization of medical practice» as part of the Antillean Exporter Plc. (Antex), the Cuban corporation that hired him as a psychiatrist from 2013 to 2015.

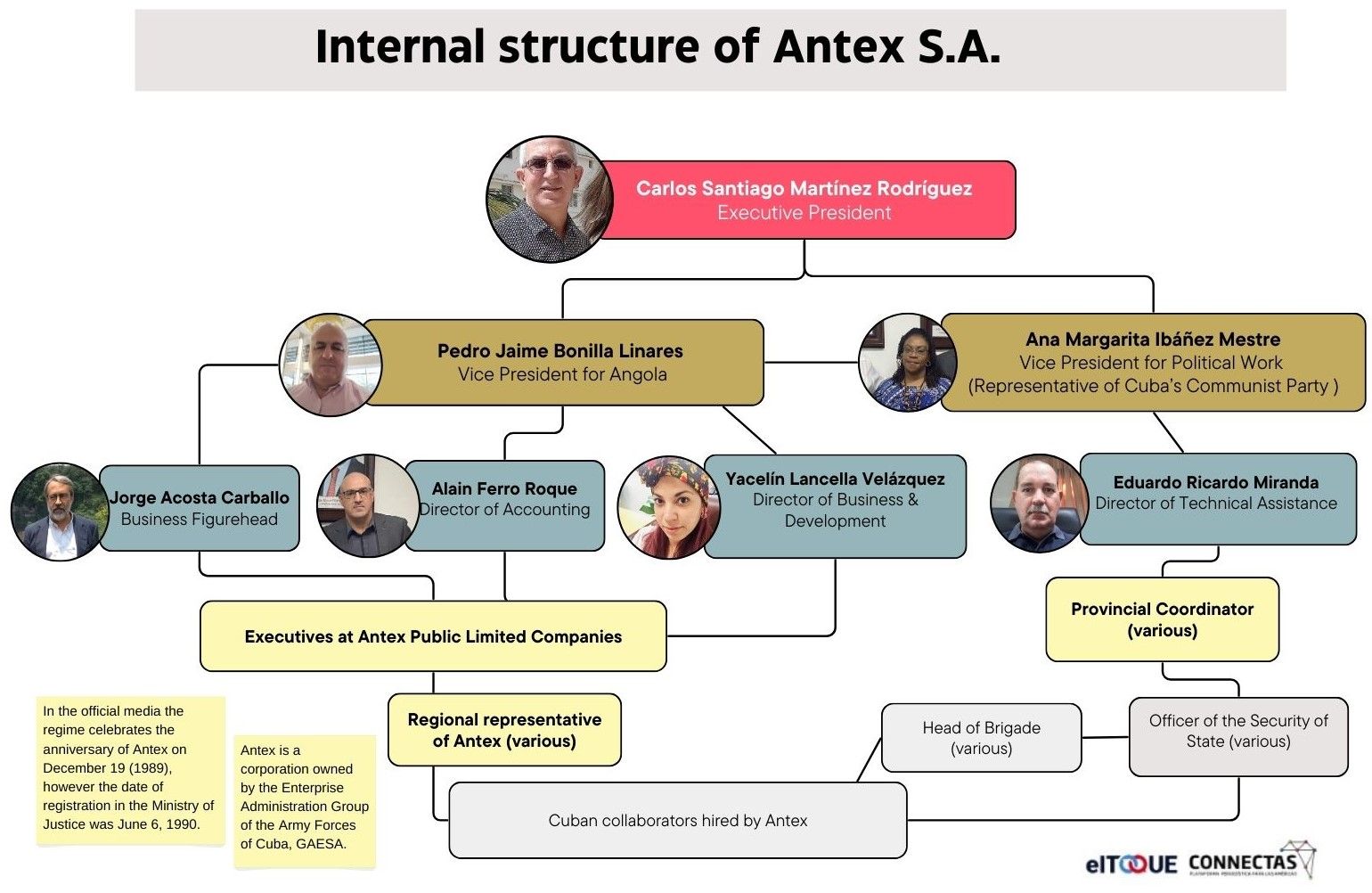

Antex is the operational arm of the Enterprise Administration Group (Gaesa), a business conglomerate of the Cuban Armed Forces, and has been in the African country starting in 1989 when it began to replace Cuban troops with the commercialization of goods and services, as well as the representation of Cuban businesses and institutions abroad. Arteaga was just one of its many thousands of employees.

«The soldiers will leave one day, but the doctors, (...) the teachers, (...) the collaborators in construction and other spheres of the economy and services of Angola stay on», Fidel Castro said in 1986. Castro was the architect of the «business of solidarity» that today «cultivates» healthcare where he once «planted» weapons. The main mission, more than international aid, is to raise dollars and to garner diplomatic recognition. The handicap is that «it fundamentally depends on the human trafficking scheme», adds Maria Werlau, executive director of the NGO Cuba Archive, based in Miami.

More than 30 000 Cuban professionals provide services in 70 countries, an economic activity that has been the main source of income for the Cuban government since 2005. Angola is the second market — after Venezuela — with the greatest strategic importance for Havana, explains Maria Werlau. There, where Antex concentrates at least 34 % of Cuban aid workers in Africa and 36 % of its doctors abroad, Cuba has managed to «project its political, ideological and military influence in a transcendental postcolonial struggle, while obtaining important benefits», observes Werlau.

The presence of the Cuban army in the African country has evolved since the sixties and solidified with the military intervention in the Angolan civil war from 1975 to 1991 — officially called «Operation Carlota» — after a runaway slave. For Fidel Castro, the African continent was then «imperialism’s weakest link», due to the absence of a robust bourgeoisie that could stop the transition from quasi-tribalism to communism.

In 16 years, Cuba deployed some 300 000 military personnel and 100 000 civilian collaborators, of which more than 2 000 died in the conflict, as per official figures. Likewise, thousands of Cuban and Soviet advisors de facto directed the Angolan ministries of Construction and Housing, Defense, Education, Finance, Transportation, and Foreign Trade, according to a report by the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

The power of Cuba's high command in the African nation was exposed after the prosecution for «high treason» and subsequent execution of several army officers, including General Arnaldo Ochoa Sánchez — Hero of the Republic of Cuba and head of the military mission in Angola — in 1989. During the trial, it was discovered that Cuba withdrew more than its fallen men from African countries such as Angola. The regime also smuggled ivory and diamonds, while conducting at the same time drug trafficking activities in America to finance military operations.

Antex, the umbrella company that brings together the commercial network of the Cuban Government in Angola, emerged shortly after the execution of the «traitor» general; in part, to whitewash the image of the island's military businessmen, who — Cuba Archive estimates — made between 4.8 and 9.6 billion dollars for sending troops to Angola. Since its founding on December 19, 1989[1], the primary objective has been — as per the employment contracts of Cuban workers in that country — «to provide clean, legal and untainted convertible currency for Cuba»; a promise that, as will be shown later on, it has not been able to fulfill either.

The great scam

«Despite being scammed and not even getting 40 % of what one should receive, we try to solve the problem anyway we can», says Maritza, a former Cuban health worker*; she adds: «We are not in solidarity with them [Angolans]; we are opportunists because we seize the opportunity to make money and to obtain, at the cost of the sacrifice of our family and ourselves, what we cannot have in Cuba even if we work our entire life».

That is why Maritza left her children in the care of her family and went to Angola, one of the best-paid international Cuban missions, where health workers like her can earn between 10 and 16 times more than their salary on the island. This makes the economic factor the main incentive for taking part in these contracts. Nonetheless, what they actually earn represents only a small part of what the receiving country pays for their services.

Based on government officials and media reports, since 2012 Angola has paid an average of 5 000 USD to Cuba as a monthly salary for each Cuban professional, although it could reach up to 7 000. The payment is by bank transfer and covers 12 months, a total of 60 000 USD. Angola’s local authorities must also provide Cuban workers with furnished accommodation with air conditioning and Internet, as well as the costs of services for the supply of «water, electricity, and fuel for domestic use», details a 2021 study on Cuban medical recruitment. That is, Cuba does not incur expenses of this kind.

Rough calculations based on the 30 131 contractors accounted for from 2012 to 2023, as per official figures, show that Antex has received around 1 808 million USD from Angola for the payment of salaries to Cuban professionals in the last 12 years.

Testimonies, reports, and employee contracts indicate that, at least from 2005 to 2014, the military-owned company paid monthly salaries of between 200 and 685 USD to Cuban technicians and professionals in the fields of Education, Medicine, and Culture.

Antex payments did not follow the salary scale from 630 to 1 200 USD USD that, as early as 1977, Angola set for Cuban graduates of technical and university careers, according to the Special Cooperation Agreement that guided the relations between both countries in matters of Compensated Technical Assistance.

By 2015, the collapse of oil prices and the subsequent devaluation of the Angolan kwanza caused the cost of living to become unbearable. According to Cuban collaborator Armando Valenzuela, a design professor at Huila’s Polytechnic Institute during 2015-2016, «sometimes there were problems with payment, it was delayed or they hardly paid anything». In theory, Valenzuela earned 500 USD per month, which was 100 less than the salary of art historian Anamely Ramos.

Of the total, a maximum of 200 was the actual amount they got paid in cash. «A pittance», said Ramos. «The zungueiras — the women who roam the streets selling products they carry on their heads — and housekeeping staff earned more than us», she added, in reference to the Cuban collaborators.

Armando Valenzuela. Huila, Angola, 2015. Courtesy of Valenzuela

In addition to the frustration over the living expenses, «modern slavery» allegations started to build up from Cuban doctors in Brazil. The situation, Arteaga reasons, led to a salary increase that year. The psychiatrist began earning 1 000 USD per month, a 360 increase from his 2013 salary when he arrived in Angola. The economic factor, he clarifies, is one of the incentives to participate in the mission.

«We always leave Cuba with the idea of making money, hoping that they’d pay us more. They never tell you how much the actual salary is until you receive the first one» — confirms Dr. José*, a former member of the Cuban medical brigade in Angola. «I think that, in 11 months, what I managed to save was perhaps 10 000 CUC», he reckons. The CUC was Cuban convertible currency from 1994 to 2020 equivalent to USD; later replaced with the current virtual dollar, the MLC.

Information gathered from 7 121 payroll slips and 189 statements of accounts of collaborators in Angola issued by Antex, as well as through those who were and are currently on mission, demonstrate that monthly salaries range mostly between 500 USD and a maximum of 1 200. The average salary is estimated at 750 USD.

The appropriation and embargo of the worker’s salary is, by far, the most lucrative source of income for the Cuban regime, through Antex, in Angola.

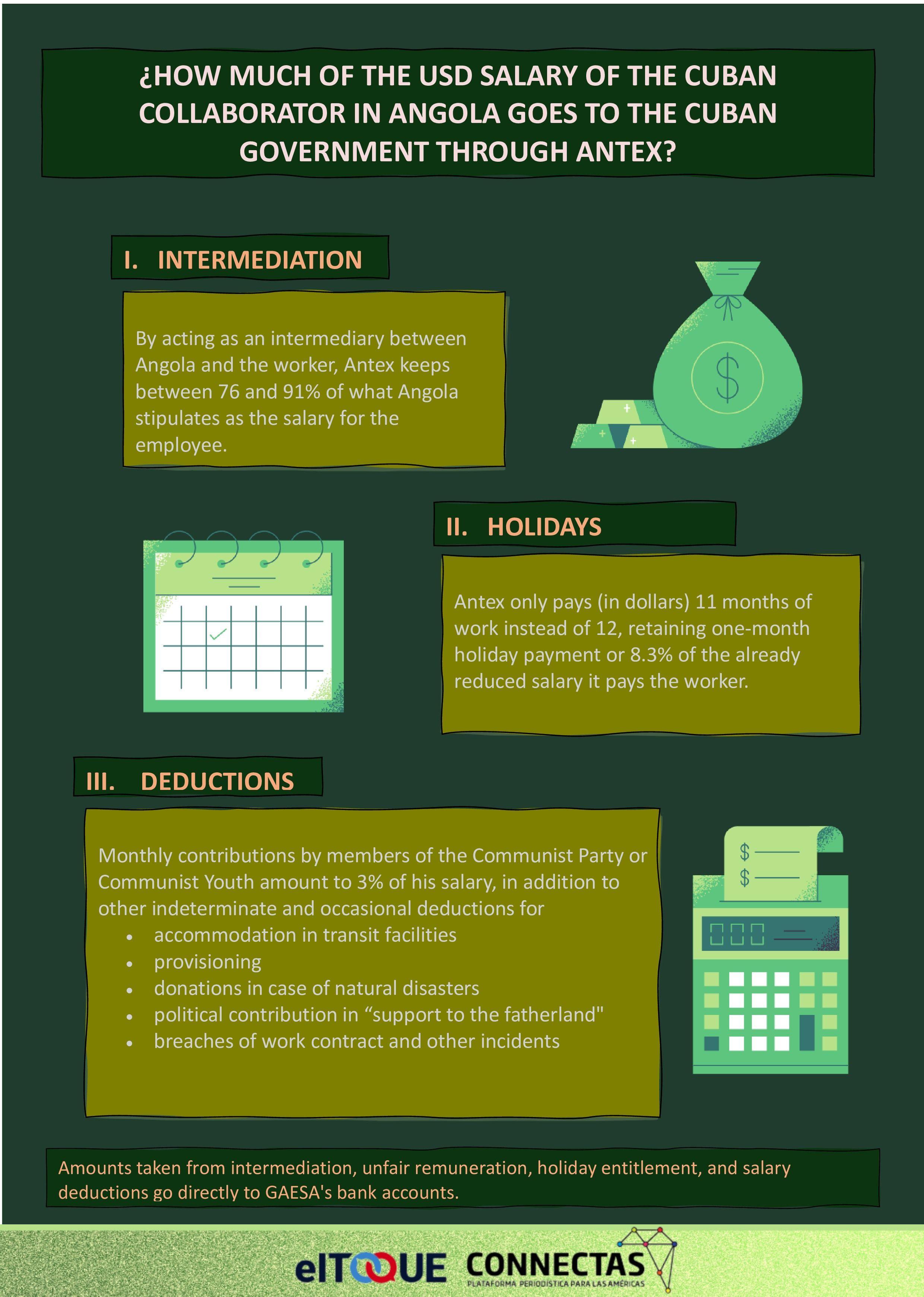

Antex gets the biggest dividends for serving as an intermediary between the Angolan Government and the Cuban worker. By means of representation alone, the Cuban State gets between 76 % and 91 % of what Angola pays per collaborator. In other words, no collaborator has received more than a quarter of what Angola paid for their work.

According to first-hand accounts, the corporation does not provide employees with their payslips. These are only for internal use by the Antex officials who, exceptionally — and often at the request of the collaborator — can provide them with a printed Statement of Account with the breakdown of the financial movements associated with their salary in Angola. «They gave it to me twice and it was when I was on vacation. They also give it to those who are finishing their mission», explains Sergio*, who worked in 2023 at the Meditex Clinic, a private health center owned by Cuban military conglomerate Gaesa in Luanda.

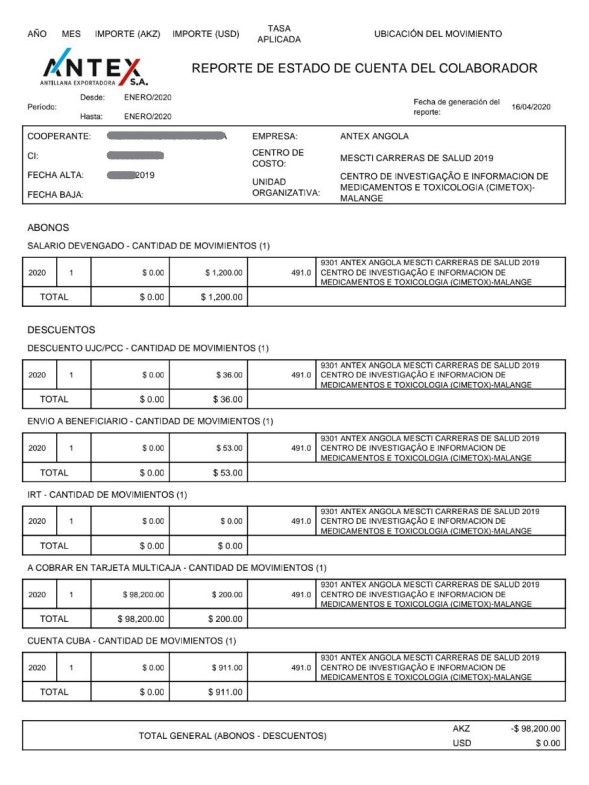

A statement of account of a Cuban doctor issued by Antex in 2020 shows gross nominal salary of 1,200 USD and monthly discounts as follows: for payment to the Communist Party (36 USD), for sending remittances to the family in Cuba (53 USD) and for maintenance or stipend in Angola (200 USD converted into kwanzas). The actual amount that goes to the worker’s account in Cuba is 911 USD converted to CUC, Cuban convertible currency in force from 1994 to 2020. (Courtesy of a source close to Antex.)

The collaborators can't access their current account in Cuba either — which is designated exclusively for the deposit of the nominal salary — and cannot know how much they accumulate each month. The work contracts stipulate that the worker must «irrevocably» grant Antex even «the power to withdraw from the deposit account the amount necessary to cover compensation derived from the application of disciplinary measures».

Antex's official documents demonstrate the reluctance of the Cuban corporation to remunerate its workers accordingly while taking possession of most of the dollars earned by Cubans on official missions in Angola. But this is not an isolated case.

Cuban aid workers are in a similar situation in other oil-producing countries such as Venezuela[2], whose intermediary is another company on the island, Cuban Medical Services (SMC). Even in Saudi Arabia and Qatar, where intermediation is not allowed, Cuban professionals must transfer 80 and 90 % of their salary, respectively, to an account stipulated by the Cuban authorities.

More for the government, less for the worker

In addition to plundering as an intermediary, the regime has a second way of extracting money from its human resources, through the holiday entitlement. Instead of paying 12-month work in US dollars, Antex only pays 11 which represents a profit of 8.3 % for the company on top of the representation charges.

In turn, the annual leave is paid, not in USD or convertible currency, but in Cuban pesos, based on the salary in Cuba, which does not even represent 7 % of that earned in Angola, according to the individual contracts.

A third method for confiscating money from the salary of the workers is via deductions. «The members of the PCC (Cuban Communist Party) have their Party fee deducted», explains Dr. Arteaga. This type of reduction — also applied to members of the Young Communist League — ranges between 3 and 10 % of the salary, which, at a minimum, reduces income by 28 USD per month for those earning 950 USD. Such was the case of Maritza, who lost, according to her own records, «more than 1 000 dollars» due to Communist Party contributions in the three years she was hired.

Other collaborators mention pressure from the mission leadership to make «donations» to Cuban state accounts in Cuban convertible currency (now MLC) in cases of natural disasters or unfortunate events on the island. Every year, they also must make their «contribution to the fatherland»; Sergio explains in this regard: «They will deduct something from your account, you choose whether it is 5 dollars, 10, 20 or whatever».

Likewise, travel and lodging expenses prior to departing from Cuba, in the case of collaborators who reside outside of Havana, are also subtracted from the monthly salary in dollars.

«They even ask you if you need transportation from your province to Havana and they provide it for you, and the same goes if you need accommodation as well. Then they will deduct all of this from your first salary in Angola», explains Dr. José.

According to a Facebook post by Dr. Maria Carla Bonachea, Antex charges «for breakfast or snacks» and lunch, as well as for bed clothing, in the transit hostel. Bonachea also highlighted «the horrible living conditions in that place».

A former Antex official, who wishes to remain anonymous for fear of reprisals, confirmed the above: «They charge you for a mosquito net, a set of sheets, and the snack they give you at the hotel», although judging by Antex regulations for collaborators, the mosquito net is free. The rest of the products (toothpaste, towel, bed covers, and a sandwich with a soft drink) must be paid for. In the payrolls issued by Antex, the items appear enclosed in the «Clothing» category amounting to 19.80 USD.

There are further deductions that reduce the amount deposited in the accounts in Cuba and, consequently, the total savings at the end of the mission.

While in Angola, the 200 USD monthly allowance for living expenses includes one payment upfront (and later deducted) which, according to the employment contracts, is taken monthly from their nominal salary, and not as an extra payment. In practice, Sergio explains, the amount has been reduced to 100 due to the corporation's financial constraints. Armando Valenzuela, states that, in his case, the corporation also subtracted the equivalent of «50 dollars» for family remittance, a transfer to help a relative of his choice in Cuba. Each monthly transaction carries an extra cost for the worker.

It is noteworthy that the company never pays in dollars. Instead, it hands over kwanzas in Angola, at the rate established by the company, and deposits convertible currency on the island (today MLC) at a 1x1 rate in a «frozen» bank account. The big drawback is that the collaborator must then buy dollars to acquire goods in Angola that are scarce in Cuba.

The military company also determines how much money the worker can withdraw and when. Individual contracts establish that withdrawals can be made on only two occasions: during annual vacations (when they can withdraw up to 50 % of the balance), and at the end of their mission, (when they can withdraw the entire accumulated amount).

Based on the 750 USD gross average salary and the previous deductions, the rest of the money would be the equivalent of 477 per month (or 5 724 per year) which should have been, in theory, the net monthly salary deposited in Cuba, up to December 2020.

Starting in 2021, the changeover from convertible cash (CUC) to virtual currency (MLC) caused, overnight, a 56 % loss of employees' salary deposits in their frozen accounts on the island. This was done by converting the CUC they had into Cuban pesos (CUP) or «useless pieces of paper», as Maritza said, at a rate of 1 x 24. The news, distributed in a Circular to Cuban collaborators, was seen as a scam by Dr Bonachea who shared it on Facebook.

With the new measure, the average savings after 11 months of work became 125 928 Cuban pesos or USD 2 518.56, at a time when one dollar was valued at 50 CUP on the informal currency market.

In other words, because their salary was paid in Cuban convertible currency as opposed to dollars, and because Antex only pays 11 months of work instead of 12, the employees lost the equivalent of 3 205.44 USD from the 5 724 USD that they should have saved in a year.

What was left in their bank accounts at the time represented 4 % of the USD 60 000 that Angola pays Antex per worker per year. However, the Cuban peso has continued to devalue rapidly since 2021, so much so that, at the time of publishing this research, 125 928 CUP only amounted to 367.14 USD.

«Then, when you thought you had money, you were left with nothing. It was the most unfair thing in the world», said Maritza.

As a result of the inflationary process on the island — which exceeds 335 % from 2021 to the end of 2023 — those currently working in Angola have seen the purchasing value of the Cuban peso reduced by 65 % and the value of their savings has plummeted accordingly.

In terms of real income, due to inflation, the 950 USD that a nurse earns as a gross salary, for instance, is really worth about 617 or even less, judging by the instability in the exchange market.

Regarding the payment mechanisms that Antex uses, Julio Antonio Fernández Estrada, a PhD of Legal Science said that they constitute a clear violation, «a way of controlling the worker by controlling their salary and, worse, their bank account». Fernández said that these are «immoral contracts» in which «the employer behaves like a feudal lord».

Antex: the exploit

Antex also charges for the transportation of household goods to Cuba: Cuban professionals in Angola must pay the company for their luggage during vacations and for their cargo at the end of the mission. The shipments may include cookers, ovens, refrigerators, televisions, and computers, among other equipment that they cannot buy at an affordable price in Cuba. In some cases, imports have taken up to three years to be transported to the island, as per reports by those who are affected by this issue.

In other cases, they have received only part of their cargo or «boxes that no one knows to whom they belong», former healthcare workers complain. Of the 31 containers that were «lost» in the midst of the pandemic, 11 are still «sailing». Judging by a communication from Antex to a group of affected parties accessed by elTOQUE and CONNECTAS, the company cannot ensure that the 394 «packages» that remain to be delivered to former collaborators are stored there.

A source close to Antex confirmed that in total there have been «200 collaborators with pending shipments since 2021», for which they paid «between 5 000 and 10 000 USD» to the military corporation for transportation to Cuba. This is a done deal for the Cuban State.

«Antex's framework is based on what it takes from collaborators. They [the bosses] do nothing, it is the collaborators who do all the hard work so that the military and those from State Security live at their expense while controlling them (...). And everything happens with the consent of President [Miguel] Díaz-Canel», the source stated.

In addition to the corporate structure, there is a military attaché, Colonel Enrique Kindelán Delis, as of December 2023. Sources: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Cuba, Antex platforms, documents, and officials, as well as testimonies of Cuban collaborators in Angola.

Cuba’s lucrative «business of solidarity», greatly favored by the Angolan Government, has left Angolan professionals underpaid or unemployed. This has come as a shock to the educated Angolan workforce, many of whom have studied in Cuba, just as their colleagues from the island, but not tuition-free. The Communist government charges Angola 18 000 USD per student per year, resulting in significant profits totaling around 111 million USD from 2018 to 2022 — which represents a fifth source of income for the regime.

This form of discrimination has been pointed out and criticized by independent professional unions and organizations. The Angolan Medical Council, for example, questioned the decision of its Ministry of Health, Silvia Lutucuta, to pay 5,000 dollars for the salaries of Cuban colleagues while they are paid eight to ten times less and many are unemployed, said its president, Dr Adriano Manual, in 2020. He also labeled the presence of colleagues from the island as «a business», a way of «stealing public money» through the hiring of doctors who arrive as specialists, but who are not specialists, while others «are not even doctors», he stated.

However, the amount that Angola pays Antex per doctor was justified by the country's Minister of Health. «The Cuban professionals came to perform a double function, to train Angolan personnel and to provide assistance», she said at a press conference. Both services are paid separately, according to some twenty legal documents revised for this investigation.

Dr. Arteaga — founder of the psychiatric services in Malanje province, where he provided medical care and training — was only partially paid for his work. The salary that Angola allocated to remunerate his teaching duties «went in full to [Cuba’s] Armed Forces», he says. «They told me that I had my allowance for attending patients and that had to suffice because the rest was for the homeland». In the homeland, however, investments between 2018 and 2022 in Public Health and Social Assistance barely averaged 1.7 % of the income generated by the export of medical services; while tourism continues to receive 18 times more, according to official figures available so far.

The business of human trafficking

«Forget about scientific titles and academic degrees... Here everyone will earn the same and will be relocated according to the interests of Antex management. You are civilians employed by the Army and you must obey as such», shouted an army officer to a group of Cuban doctors in Luanda, recalls the psychiatrist.

Working as a civilian for the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Cuba in Angola is not very far from the role of being a soldier, whose duty, above all, is to follow orders. Obedience is what Antex expects from its employees who are bound to non-negotiable contracts and placed in posts for which they are not always qualified. «They placed me as a pediatrician and my job was to treat children, even though I am a general practitioner», confirms Dr. Jose.

In a 2020 interview, Neurosurgeon Armando Aleman, who worked at the Maria Pia public hospital in Luanda between 2007 and 2011, described how non-Cuban colleagues perceived Antex's questionable treatment towards its subordinates. «An anecdote summarizes my experience on the mission. They take us to the Slavery Museum and the guide explains to us from where the slaves were shipped to America; I remember that an Angolan surgeon told me: “now the slave's embarkation port is at the José Martí Airport”» — in reference to the Havana International Airport.

According to a study on the business management of the military corporation published in the Journal of Social Sciences in 2021, Antex perceives as «threats» the «legislative transformations and generational changes in Angola» (which endanger the privileges hitherto held by the island in the African nation), as well as the «flexibilization of the Cuban migration policy» (which provides other options to the workforce outside the control of the Cuban State).

Even after leaving the mission, Antex considers the professionals as if they were its property. Marcos Elias Aguilera, a military doctor in Angola from 2009 to 2011, nearly lost a second-hand car that he had bought with his savings, just because he requested to be discharged from the army. «A General appeared in my unit to tell me that they would take away my car (as if it had been a gift)... they discharged me and I was able to go to a polyclinic as a civilian doctor», he told the organization NoSomosDesertores (We are not deserters).

For Fernández Estrada, it is clear that «the state treats the Cuban workforce as its own» and «bases its impunity» on the «lack of transparency and the needs of the contracted personnel». According to the Cuban attorney, workers «prefer to endure exploitation and become victims of trafficking rather than lose the possibility of traveling and having minimal economic gains that Cuban workers do not have».

The large-scale export of services — which supports the Havana regime and is the matrix from which the business network in Angola springs forth — «creates a dangerous situation for large numbers of Cuban workers who accept an irregular labor regime and receive very few assurances for the exercise of almost any right», he added.

The practices that the Cuban military engages in for hiring and maintaining the flow of workers in Angola and how they establish suitability criteria, are based on subjective perceptions and political biases, rather than professional capacity, and contradict the provisions of the WHO Global Code of Practice for the International Recruitment of Health Personnel, as well as the legislation of the International Labor Organization.

According to the work contracts, Antex requires workers to be committed «to the country, its people, and the leadership of the Corporation», and to maintain a «revolutionary behavior» in line with the socialist system. It also calls for austerity, «dedication» and asks for any «sacrifices deemed necessary on an individual level».

The review of 7 310 salary payrolls and account statements of collaborators issued by Antex confirm that nearly 40 % of those hired were members of the Communist Party of Cuba, in spite of the fact that only one in ten Cubans belongs to the PCC. Such a high percentage of militants — who pay 3 % of their USD salary to the party — shows the politicization of the international mission and the need to extract as much money as possible from its workers.

In order to maintain its recruitment scheme, the Cuban regime has legally shielded itself to conveniently retain workers while instilling fear in them. Migration Law No. 1312 prohibits entry to Cuba for those who abandon their contracts and settle in a third country. It also restricts the rights of professionals to leave their country (except for the fulfillment of state missions) because they are deemed indispensable. Meanwhile, article 176 of the Criminal Law penalizes with sanctions of between three and eight years in prison for the abandonment of duties — a measure in force since 1986 and renewed in 2022.

Fernández Estrada considers mobility limitations a «political weapon» because «they are used as a threat, as a persuasion mechanism, as punishment, as psychological torture». Likewise, prohibitions are not always applied with equal discipline, but are activated depending on the context.

«Discretionary enforcement is a feature of the application of law in authoritarian regimes», the attorney points out. Such legal shielding is based on a «political decision to confront the migration of thousands of people to the United States and other countries as a war contingency and as a matter of national security», explains Fernández Estrada.

In Angola, Dr. José had to report every step he took and could not freely leave Malanje, the town where he provided services. «If you have to transfer a patient, first you have to notify them and then you get on the ambulance», confirms the doctor, to whom Antex confiscated «80 % of a month's salary» for traveling to a neighboring municipality without authorization from his superiors. According to the guidelines issued by the Antex leadership in July 2020, to which elTOQUE and CONNECTAS had access, travel outside the municipality must be «authorized by the representative» of the corporation and the command post must be informed of the «date and time of departure and return».

Although it violates Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the restriction of mobility in missions is further validated by internal regulations issued by Antex, cited in the 13th report of the Observatory of Academic Freedom (OLA). These come from Resolution 168 of 2010 on disciplinary rules for collaborators in general — which limits the rights of aid workers to interact with persons outside of the mission and to express themselves freely.

From his time at the Higher Polytechnic Institute of Huila, Armando Valenzuela remembers that they «could not talk about the case of Cuban General [Arnaldo] Ochoa» or his participation in the war in Angola. It is also considered a breach of employment contract to accept gifts, spend the night away, receive visits from people outside the mission, or give statements to the press without authorization from management.

«They make you do jobs that are not specified in the employment contract, such as … voluntary work as if you were in Cuba», as well as acting as a security guard at his Clinic during the days following 11J anti-government protests on the island «in case there were any demonstrations by independent Cubans», says Sergio*. Political reaffirmation events were also held in other cities, while commemorative events of this nature are frequent in the mission.

The interception of private communication and correspondence is also another pattern of the Angolan mission, thanks to the fact that the IT staff working for the company «know the Internet connection password and have access» not only to Meditex computers but also to private devices, explains the healthcare worker: «If they find something that seems suspicious, the security people will immediately call you and suspend your Internet». He adds that the feeling of being constantly watched «is really stressful».

Another «violation of the provisions» imposed by the military in the employment contract is «establishing marital relations abroad» that may lead to the formalization of a relationship, pregnancy, or «the recognition of children», which is based on racist criteria.

According to Fernández Estrada, such a violation of privacy undermines the right to marriage and to have a family established in Article 16 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Punishment for breach of contract or indiscipline includes, in addition to total or partial confiscation of the accumulated salary in Cuba, the termination of the contract. Reports, testimonies, and media coverage on the subject have previously documented penalties as a pattern in the international provision of professional services under Cuban state companies.

Valenzuela and Arteaga — both exiled in Madrid and considered «deserters» and «traitors» by the Cuban regime — experienced it firsthand. Neither of them remembers the exact amount they left behind, but they estimate it was thousands of dollars. «In Angola, I felt suffocated. I was drowning, it was a state of oppression that made me ask myself “what am I doing here?”», explained the psychiatrist.

It is estimated that at least 10 000 Cuban aid workers have been impacted by the Cuban Government's regulations on freedom of movement, facing an eight-year ban that prevents them from entering the island; among them, the more than 2 500 doctors who refused to return to Cuba after the «Mais Medicos» program was repealed in Brazil in 2018 and the 8 000 health workers who between 2006 and 2017 fled missions and took refuge in the United States, protected by the extinct «Cuban Medical Professional Parole».

«The characteristics of this type of employment relationship are a lack of transparency, impunity in treatment that violates workers' rights, minimal access to justice and procedural and institutional guarantees, as well as political and repressive control of the workers' movement», says attorney Fernández Estrada.

Not surprisingly, one of the causes of abandonment of international missions is the constant surveillance and distrust of the leadership towards its employees — which goes hand in hand with the demands for them to generate more income, even if it means altering the statistics. «The Government of Angola was paying you to care for 100 [patients] and if the 100 were not there, you had to say that you had cared for that number», says Dr. José.

Arteaga had a similar experience: «There were goals» that the bosses «required to meet or inflate». At Meditex, the military imposes economic goals on the healthcare workers. This means each doctor must declare a medical care turnover of at least «80 000 USD per month», recalls Sergio. «They call you up during morning meetings for you to explain why you don't make that much money, even knowing that there are no patients and that you don't have the necessary medical resources», he explains.

Production quotas and overexploitation are then translated into propaganda. According to the Cuban ambassador to Angola, Oscar González, Cuban doctors have performed more than 48 million consultations, 118 000 surgical procedures and have made it possible for 53 039 citizens to recover their vision.

The figures are used to overshadow claims of human trafficking by magnifying the image of solidarity that the Cuban Government sells to the international community. The mistreatment and lack of legal guarantees, added to the precarious conditions of the health system in Cuba and the unpaid danger faced by collaborators under state contracts in other countries, have triggered the exodus of professionals from the sector by more than 76 000, in the last two years alone, according to data from the National Statistics Office (ONEI). A similar phenomenon occurs in the educational sector, with a deficit of over 17 000 teachers in the island's institutions in the current school year.

Added to the above is the high personal cost that «international aid» has meant for the Cuban professional for whom his government also makes it very difficult to contract independently, which entails «limitations of rights to the point of reproducing semi-feudal servitude labor practices», says Fernández Estrada. As a result of the negligent treatment by the Cuban military leadership, the safety and health of workers is compromised.

Collateral damage: family and death

The lack of transparency of the Cuban Government — based on hiding anything that could compromise the image of the healthcare superpower, in order to sell it in dollars — explains why the official discourse has never published the number of Cuban professionals who have become ill and ultimately died either in the fulfilments of these missions or due to causes attributed to their work.

However, during the course of this investigation, at least four deaths from coronavirus were found between 2020 and 2021 in Angola. Two of them — the anesthesiologist José Alberto Alonso Méndez and the dermatologist Francisco Nelson Matos Figueredo — have not yet been repatriated to the island.

The third deceased is the architect Carlos Alberto Odio Soto, whose death occurred in August 2021. A native of Santiago de Cuba, Soto was a professor at the Huambo campus of the Agostinho Neto University. Four months earlier, Matanzas urologist Alberto Alcántara Paisán had died while providing services at Benguela General Hospital and at the Faculty of Medical Sciences of the Katyavala Bwila University (UKB). It has not been yet verified whether the bodies of Soto and Paisan are also awaiting transfer to Cuba.

A person close to Dr. Matos indicated that the Cuban authorities, citing the International Health Regulations (IHR), warned the relatives that his transfer had to «wait five years because, since he died of COVID-19, that is the procedure».

The IHR, the WHO's legal instrument to prevent the international spread of diseases, was never an obstacle for the repatriation to Cuba in April 2022 of the bodies of four collaborators who died in Equatorial Guinea in 2020 and 2021. Only in the aftermath of the media expose were they returned to the island.

With the end of the pandemic declared in May 2023, there is no health excuse to delay the transfer of the bodies to their country. However, five years is the deadline «to exercise any right emanating» from the Life Insurance Policy that the employee is obliged to purchase before leaving Cuba for Angola, which provides coverage in the event of death or permanent disability. Health coverage claims could range between 25 000 and 70 000 pesos, according to collaborators and information from the Cuban National Insurance Company (ESEN).

Likewise, an unknown number of collaborators have become sick and died from malaria in Angola and across the African continent, where the disease, transmitted by mosquito bites, is endemic and widely normalized «like a cold», according to interviewed collaborators.

Based on a 2022 report from the WHO, Angola is among the five countries in Africa with the highest incidence of the disease and one of the top ten in mortality rates.

It has not been possible to verify the existence of beneficiaries (whether these are employees or their relatives) for any of the policy coverages. In some cases, those involved said they had not received compensation, and, in another, the family declined to respond. What became apparent was the obstacles that Antex imposes to reimburse the cost of drugs to its collaborators, sick with malaria, typhoid fever, chikungunya, and cholera. According to a communication from the corporation's Technical Assistance department, the following requirements need to be met:

- Letter from the Provincial Coordinator certifying that the worker was indeed treated.

- Report of the Medical Commission of the province with the diagnosis of the disease and the prescribed medications.

- Invoice from the Pharmacy where the medication was purchased which must include the Identity Number and name of the worker.

Both deaths and illnesses, as well as the impact on family dynamics, make up, without a doubt, the most sensitive side of the humanitarian tragedy associated with the provision of Cuban services abroad, and yet the State chooses to ignore it.

Since at least 2005, organizations such as Human Rights Watch have documented «the involuntary separation of many Cuban families» as part of «repressive rules for doctors working abroad» that have caused «incalculable» emotional damage. In 2022, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child also drew attention to the consequences of forced separation for parents and children.

Ironically, in the 1977 agreement on the conditions of the provision of services by Cuban technicians and professionals in Angola, the government of that country established the accompaniment of the immediate family of the collaborator (spouse and up to three children), something that the Cuban Government does not authorize. The reason — explains María Werlau — is to keep the family hostage on the island so that the professional is forced to return to Cuba and continue his service to the system.

Therefore, mothers and fathers must leave their children in Cuba because the island's authorities «do not even leave that decision in the hands of the collaborator», says Anamely Ramos, who was hired by Antex when her son was three years old and spent almost two years without seeing him.

According to Fernández Estrada, separation of the family by way of the decision of the employer is «absolutely illegal, unconstitutional and contrary to international law»; while it amounts to «further evidence of a relationship of servitude».

On November 2023, the United Nations, for the third time since 2018, transmitted to Cuba allegations of «exploitative working conditions in destination countries abroad» and «dangerous and unhealthy work environments» for collaborators. In a 2019 publication, the rapporteurs on contemporary forms of slavery and human trafficking spoke of «forced labor» in the regime of Cuban collaboration brigades. Moreover, since 2014 the international organization noted the «withheld» of the passports of collaborators on missions, the impossibility for them to choose «their place of residence or refuse conditions of work», and the payment of only a «small portion of the wage agreed upon by the governments who are parties to the cooperation agreement».

In Angola, the collaborator has the passport in their possession «because the work visa is there (...) and you always have to go out with it in case the police stop you», explains Sergio. The OLA report and the former Antex official confirm that at the airport in Cuba, upon arriving on vacation, they take away the passport of the aid worker to prevent them from abandoning the mission mid-term or from «traveling to any visa-free country». Since many of them are «regulated» (prevented from leaving the country for non-official reasons), they are not allowed to have the document. The sources consulted agree that in other missions (Venezuela), the authorities collect passports at the place where services are provided to avoid abandonments.

However, Elier Plana, hired as a computer science professor at the Higher Institute of Moxico from 2014 to 2018, recalls that after the escape of a colleague, the Cuban bosses «withdrew the passports» in Angolan territory, which caused him inconveniences by making him effectively undocumented.

Regarding living conditions, the engineer mentioned that he was «without electricity and running water for more than 47 continuous days» because the local authorities — responsible for «rent, electricity, water and other expenses of the collaborators» — diverted resources «for personal use». He then clarified that «not all accommodations had the same conditions».

Despite direct recommendations from the UN since 2017, Cuba does not have an updated legal framework on forms of slavery and, consequently, its government is not considered a facilitator of trafficking. In other words, there is no political will to eliminate the scourge in international collaboration brigades.

The most recent alarm from the international organization is preceded by the European Parliament's historic condemnation of Cuba and by the ruling of a Brazilian judge in 2016, who after two years of hearing complaints, considered Cubans working in his country «a form of slave labor». Another precedent was the lawsuit in 2018 by four doctors against the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), considering it a facilitator of the Havana regime's «human trafficking network». PAHO has had similar participation through triangular cooperation in Angola, which could open the way to a new judicial process. In recent years, other organizations such as the Cuban Human Rights Observatory, Human Rights Foundation, and Prisoners Defenders have joined in documenting and compiling complaints on the subject.

Since 2019, the US State Department has kept Cuba on Tier 3 — the most severe — of countries that do not cooperate to eliminate forms of slavery. In the 2023 Report on Trafficking in Persons, Washington denounced that «the [Cuban] government used its legal framework to threaten, coerce, and punish workers and their family members if participants left the program» of international cooperation.

«I lost my mother while I was in Angola, on Mother's Day. She had abdominal pain and died within 72 hours, at the Puerto Padre Hospital [Las Tunas], due to peritonitis. I couldn't go to see her. I had only one month left to finish the mission and if I had gone to Cuba sooner…» says Dr. Arteaga without finishing the sentence. Being caught up in such a dilemma between burying his mother and losing the two-year salary leaves no room for eloquence.

Then he continues, with a broken voice: «I wouldn't have made it (...); so, you see, I didn't desert the mission previously out of fear that something might happen in Cuba, and I wouldn't be able to be there... And look what life brought me. I lost her while I was away. For me, Angola has left a mark of great sadness».

*Maritza, José and Sergio are aliases to protect the identity of the Cuban health workers and former collaborators, who fear reprisals from the regime. For their safety, details of their current places of residence are also concealed.

[1] In Spanish, Corporación Antillana Exportadora, S.A. (Antex). The official media marks the anniversary of Antex on December 19, (1989), however, the registration in Cuba’s Ministry of Justice appears on June 6, 1990.

[2] Werlau, M. (2019). Cuba's intervention in Venezuela. A Strategic Occupation with Global Implications.

This is the first of two-parts investigation Cuba's mission in Angola produce with the support of CONNECTAS.

https://eltoque.com/en/cubas-mission-in-angola-II-the-corporate-web