Marianao, 6:07 AM. Julio stirs in his bed when he hears a notification on his phone. It’s a WhatsApp message that has a super compressed file. Mobile data works better at this time to download it.

He’s had a bad night’s sleep. His mother, a 76-year-old woman who has Alzheimer, slipped in the bath and had an uneasy night.

It isn’t easy being blind in Cuba, but Julio Vargas is. He has been living alone with his mother for the past 20 years in a house they inherited from the family. The financial support they receive from two cousins living abroad helps to ease the burden a little bit, but nobody can escape the crisis in Cuba. The challenge of maintaining the house, finding food, and keeping the house clean for an elderly person is twice as hard for Julio.

It’s 6:20 AM and the young 35-year-old man, who loves the radio and once studied IT Engineering, won’t fall back asleep. He gets up with phone in hand and plays the audio he’s downloaded, before getting breakfast ready.

Between the aroma of coffee mixed and a light breeze that begins to come through the window, you can hear: “Hola, hola, it’s Luis Miguel Cruz, “El Lucho”, and this is Historias al Oido, El Toque’s weekly podcast, where we read articles without blablabla and lequeleque…”

Stories whispered into your ear

El Toque’s stories started being told in another format on July 4, 2022. The Historias al Oido podcast was conceived so that they could reach a different audience, people with a visual impairment and people who prefer listening over reading.

The voice chosen to narrate Cuba to Cubans belongs to an old media celebrity in Cienfuegos, Luis Miguel Cruz, who graduated in Spanish Language and Literature at the Central University of Las Villas, in 2000.

Known as “El Lucho”, he worked at the Radio Ciudad del Mar station on programs such as Buenas noches, Caribe, Andando and Desde aqui Cienfuegos. He also directed Cita con la juventud, Como el primer día, Unicornio, Megahits 98.9 and the award winning comedy Efectivamente, written by Carlos Fundora, the creator of the comedy group La Leña.

At the local TV channel, Perlavision, he was the first news director of Notisur and youth show De Joven a Joven. He also did voice-overs for different shows such as Semilla nuestra and news show Impacto.

After over a decade in the Cuban media, he migrated to California in 2010. In the US, he continued his relationship with channels such as Univision and Telemundo, but he ended up dedicating himself to teaching. He now teaches Spanish as a foreign or second language. He has helped many high school and university students, as well as pensioners to improve their Spanish, to write and speak fluently.

He worked on an audiovisual series for El Toque with caricatures by illustrator Wimar Verdecia about the protests that were held on November 27, 2020, July 11, 2021 and the Civic March for Change in Cuba in November 2021.

In the past year, Luis Miguel has narrated 47 podcasts in simple and complex formats; sometimes, only his voice prevails, but other episodes are more developed – and can include fragments of testimonies and other sound resources.

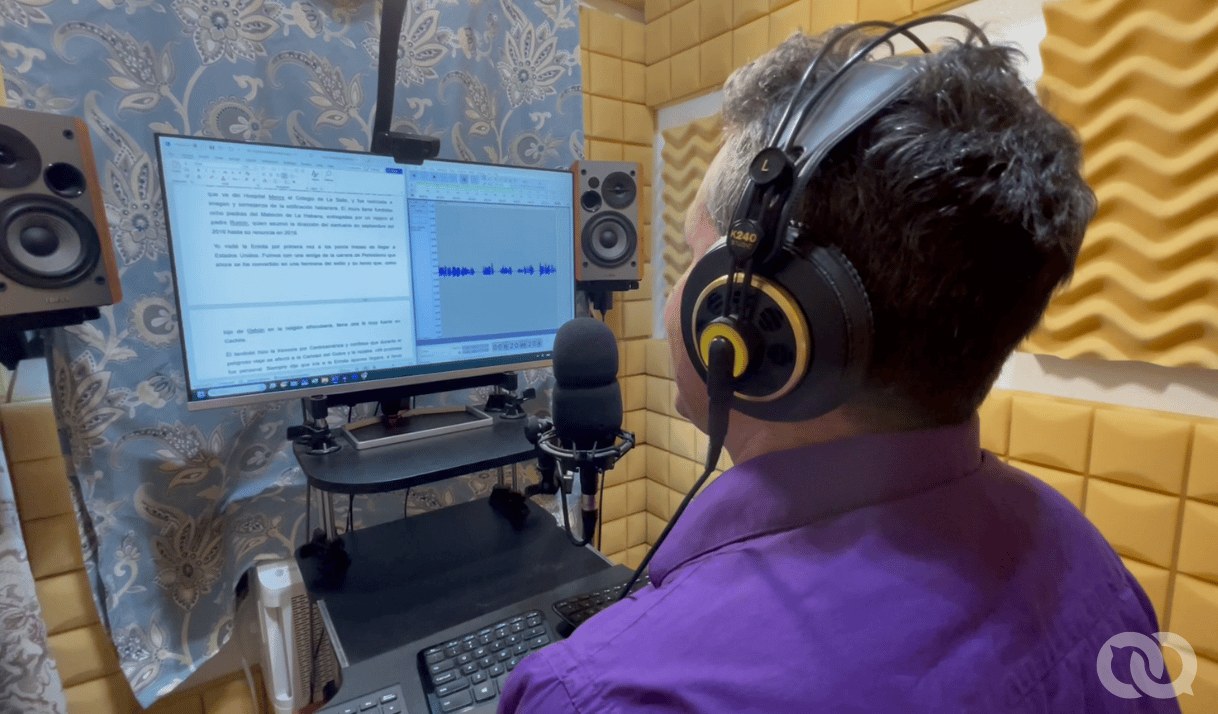

He produces all of the podcasts at home. He has the equipment, acoustics and software to record a professional narration in his home studio where – in addition to Historias al Oido – is where he also teaches online classes and records audios for his students. He prefers to record in the afternoon because his voice has warmed up by then.

“A presenter is like a high performance athlete. You have to train and train a lot to achieve your best performance. That’s why I begin my day with meditation,” he explains.

He works relaxation, articulation, diction and diaphragmatic breathing with specialized exercises. Once he records an episode, he also sees to editing it and post-production.

The hands behind Historias

Luis Miguel has two criteria when choosing an article to read: audibility and a balance of subjects. “There are articles that sound good while I’m reading them in my head. So, I say: “I’m going to read this one.”

He has read pieces such as “We have the right to return” by Cuban lawyer Julio Fernandez Estrada, who is the most listened to on the podcast platform iVoox at the moment.

He also remembers more complex episodes such as “Making a living with Garbage” (I and II), “A tribute to Pablo Milanes in Cuba and Spain: “There is still beauty in nostalgia” and “The highway as a second home: a woman in the world of heavy duty trucks.”In these episodes, music and sound effects become characters.

The authors of the articles selected for Historias al Oido are grateful for the new lease of life their work takes on through narration.

“Intonation, tone and other elements that Lucho uses when telling these stories, including audio fragments that allow us to present our interviewees with their own voices,” Rachel Pereda says, “it is a more intimate way of telling these stories and is able to transport us to this situation described in words and also to create atmospheres and stirring the public’s imagination at the same time.”

According to historian Leonardo Fernandez Otaño and journalist Laura Seco, the project has an inclusive dimension and advocates for diversity.

“An article that takes on life is joy for its author,” journalist and editor Glenda Boza Ibarra says, who appreciates the opportunity this format presents her to be doing lots of things while she’s listening.

Migration expert Loraine Morales addresses demographic issues in her articles. Reading them makes the statistics she offers even easier for the audience and are delivered in a more impactful and easy-to-understand way.

She says that “instead of presenting the numbers, this narration privides contexts, transmits emotions, establishes a human connection to these articles that are a bit more complex.”

According to Litzie Alvarez Santana, the narration of “Women’s Boxing in Cuba: better late than never?” about boxer Namibia Flores, took her back to her time in radio and the magic she finds in sound. Meanwhile, the host enjoys how authors manage to combine proper development of a story with colloquial writing.

However, according to the team that makes the Historias al Oido podcast, the most distinctive and important thing is the audience they are gradually being able to reach: people with a visual impairment.

Who listens to Historias?

In order to play Historias al Oido podcasts, Julio Vargas uses the screen-reading option on iPhone phones called VoiceOver, and Talkback on Android.

The tool describes every action he makes using the phone. It receives infomation about the actions he might make in different applications, with every swipe. It also tells him how much battery is left, the number of new messages, a notification that Luis Dener has just uploaded a new video to his YouTube video.

Julio formed the group “Podcast and more,” that compiles more than a dozen participants. The majority are blind or visually-impaired people who share audio content to keep themselves informed to enjoy their free time. They share Historias al Oido in the group.

According to Cesar, one of the group’s membeers, he was especially moved by the episode “Our Lady of Charity of El Cobre in Miami: a story of two shores,” because he is devout to the Virgin and he has never been able to visit El Cobre. He wanted to ask: “for everything we Cubans deserve, for everything we want so much and for everything I know they’re going to give us.”

Another member from this group, Lazaro Duarte, points out that the podcast shows a Cuban person’s day to day. Meanwhile, Cienfuegos resident Rolando Requesen thinks Historias al Oido” is too long and sometimes boring. Carlos Andres added Historias al Oido (2) to his Pocket Casts, a free app for podcasts, and he believes the most interesting thing is El Lucho’s narration.

Comments and suggestions from those who belong to the group “Podcast and mas”, feed into El Toque’s project. They send voice messages with their opinions, point out what could be improved without doubting. “They are a small Cuba,” Luis Miguel Cruz says, “that fits in a phone’s speaker.”

This article was translated into English from the original in Spanish.

Comments

We moderate comments on this site. If you want to know more details, read our Privacy Policy

Your email address will not be published. Mandatory fields are marked with *