Cuban Doctors in Spain: Lifeline for Public Healthcare, Victims of Bureaucratic Delays

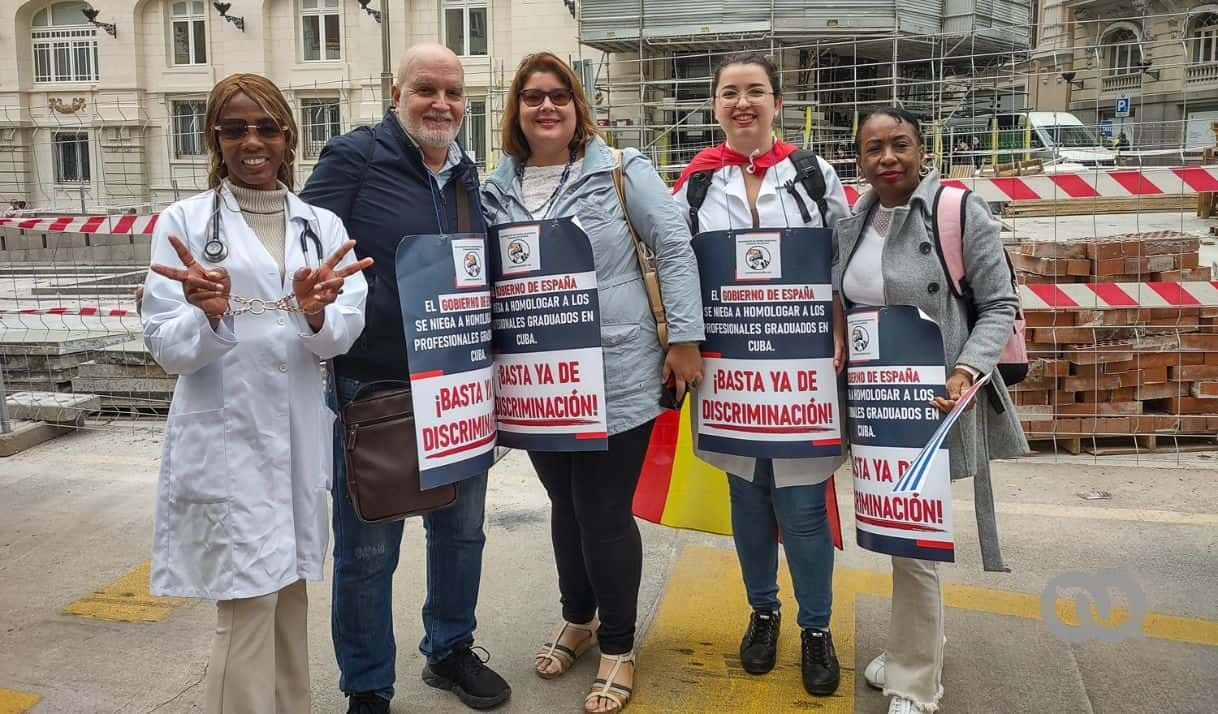

Photo: Mabel Torres

“Dealing with patients and adapting to a new healthcare system wasn’t the hard part. The hard part was waiting sixteen months for a piece of paper. A paper that said I was officially a doctor in Spain.” That’s how Cuban physician Alain Miguel Rodríguez Martín begins his story of becoming a practicing doctor in Spain, where he has lived for the past seven years after graduating in Cuba and working in Venezuela and Pakistan.

“I earned my medical degree in 2014 and completed my general surgery residency in Las Tunas from 2014 to 2017,” he recalls. The process of validating his medical degree in Spain took nearly a year and a half. “In my case, it was exactly sixteen months. Everything had to be done in person. You submitted the paperwork and waited.” After that hurdle, Alain Miguel began the process of getting his specialty recognized, but this time, he wasn’t so lucky.

He applied five years ago. The process is still ongoing, and he has yet to receive an answer. He’s not alone. “I don’t know a single Cuban whose general surgery specialty has been recognized. Some of my colleagues have been here for twenty years and are still waiting.”

Unwilling to rely on recognition that may never come, Alain sat for Spain’s competitive MIR exam—the national test that grants access to medical specialty training—four times. He eventually secured a spot in occupational medicine, but had to give it up due to the harsh conditions residents face. Living in Madrid and traveling almost 300 kilometers weekly to Albacete proved unsustainable. “I couldn’t keep it up. A resident’s salary just isn’t enough,” he laments.

This year, he tried again. He hopes to land a spot in family medicine. “It’s not what I wanted, but without a recognized specialty here, you can’t build a stable career in the public health system. And that’s what I’m after after nearly a decade here: stability.”

Cuban Doctors Caught in a Bureaucratic Maze

Alain’s story reflects a broader crisis in Spain’s healthcare system, where a shortage of medical professionals is particularly acute in primary care. Cuban doctors have become essential to keeping services afloat, especially in the Canary Islands, where the lack of family medicine and pediatric specialists is critical. There, dozens of Cuban physicians are filling in gaps in clinics and hospitals.

According to reporting from Cadena SER, over 30% of substitute doctors in the Canary Islands’ primary care system are foreign-trained, and most of them are Cuban. Out of 112 registered foreign doctors, 83 are from Cuba. Many of them practice without official recognition of their family medicine or pediatric specialties, even though they hold the required credentials and experience.

Spain faces a healthcare paradox: it urgently needs more doctors, yet thousands remain stuck in a bureaucratic limbo. Julio Roque González, coordinator of the Cuban Degree Recognition Movement in Spain and a pediatrician with over 35 years of experience, estimates that at least 3,000 Cuban professionals—most of them healthcare workers—are still waiting for their qualifications to be validated.

Though Spanish law, under Royal Decree 889/2022, mandates that such processes take no more than six months, real-world waits often stretch into years. Investigations by elTOQUE have documented cases that dragged on for more than six years.

The delays are especially frustrating given that Cuban medical programs have already been vetted by Spain’s National Agency for Quality Assessment and Accreditation (ANECA), giving Cuban graduates a theoretical advantage known as “direct recognition.” But in practice, that fast-track rarely delivers.

Frustrated by the government’s inaction, affected professionals have started organizing and speaking out. On September 25, 2024, dozens of Cubans and other Latin American professionals protested outside Spain’s Congress of Deputies in Madrid. It was the second protest organized by the Association of Cuban Doctors in Spain and the Cuban Degree Recognition Movement in a year.

In response to growing pressure from migrant healthcare workers, the Spanish government introduced reforms in late 2024 aimed at speeding up the recognition of foreign degrees. Diana Morant, Spain’s Minister of Science, Innovation and Universities, announced during a congressional appearance that over 40,000 applications were resolved in 2024—nearly double the number from 2023. The goal for 2025 is to process 80,000 cases.

A Health System in Need of Help

Despite these efforts, Spain’s Ministry of Health reports a current shortfall of at least 5,874 healthcare professionals, particularly in primary care. A 2024 investigation by El País and Lighthouse Reports revealed that six in ten immigrants work in high-demand sectors, such as healthcare, despite Spain having the second-highest unemployment rate among foreign-trained health workers in the EU.

Even without official recognition of their specialties, Cuban doctors are staffing general clinics and emergency rooms, especially in underserved areas. The Canary Islands’ doctors’ union has acknowledged that without this foreign workforce, the healthcare system would collapse.

For a 29-year-old Cuban doctor who asked to remain anonymous, the solution is clear. “Most of these vacancies could easily be filled by Cuban doctors. We’re trained to work under any conditions—with or without resources,” she says.

Her own degree validation process took two years and ten months, a period she describes as “emotionally and financially draining.” Delays also come at a professional cost. “The longer you go without recognition, the more skills you lose,” she warns. “Even if you keep studying and reviewing materials, some clinical competencies require practice. That’s something the Ministry needs to consider.”

Cuba’s Medical Exodus

For decades, Cuba has trained tens of thousands of doctors as part of a strategy to expand global influence and earn hard currency by sending medical missions abroad. While the program earned international praise during Fidel Castro’s presidency, it has also drawn criticism. Independent media and human rights groups have denounced the working conditions of these professionals, who often forfeit most of their salaries and endure strict limitations on personal freedoms.

At the same time, Cuba’s deepening economic crisis has triggered a mass exodus of healthcare workers. In 2023 alone, nearly 43,000 employees left the country’s public health system, according to official data from the National Statistics and Information Office. Thousands of those doctors and nurses are now seeking permanent residency or career opportunities in countries like Spain—hoping to rebuild their lives outside the grip of Cuba’s state control.

Comments

We moderate comments on this site. If you want to know more details, read our Privacy Policy

Your email address will not be published. Mandatory fields are marked with *