When Cuba was experiencing one of its toughest crises in collective memory, in the early 1990s, government media bent over backwards to encourage the population. It wasn’t enough to give the crisis a unique name like “the Special Period”, a euphemism to mitigate and point out the circumstantial nature of the situation, but they also put emphasis on representing that chaos with excessive optimism that we sadly carry on today.

The romanticization of poverty, also known as “dignified” poverty, was one of the resources used to call upon the Cuban people’s resistance, while they highlighted the heroism of their professional and everyday efforts. In the creation of this popular consciousness, of this bias surrounding the “revolutionary”, sacrifice was invoked with stereotypical depictions of social reality, which was reduced to a positive and sugar-coated view.

Discourse constructs reality and influences people’s actions. The Government’s ability to control grows if the media that informs us shares a single political stance and a single vision, as a result. “Voluntary” labor in the fields was presented to us in newspapers as a great merit, shampoo made with medicinal plants was sold to us as the alternative of the year and any innovation to try and ease the crisis was addressed with praise and optimism, and this really hurt us.

Three things we should bear in mind when analyzing the way our poverty has been represented in the media: triumphalism, discipline, and distraction.

If we rescue articles from the past, to understand what we’re experiencing today, we’d find phrases like: “We suffer, but support [the Revolution]. They fight, struggle, don’t become discouraged, don’t become disheartened, they are proud of what they are doing,” an article published in Cienfuegos’ weekly paper 5 de Septiembre reads, published in 1993. In fact, most of the time this everyday struggle was presented as heroism. The Cuban people’s ability to make sacrifices as a way to take on the crisis was drilled to death, as the only politically correct conduct possible, the only conduct allowed. The image of national triumph and success also implied support and loyalty to the Revolution, proof that it had to win out.

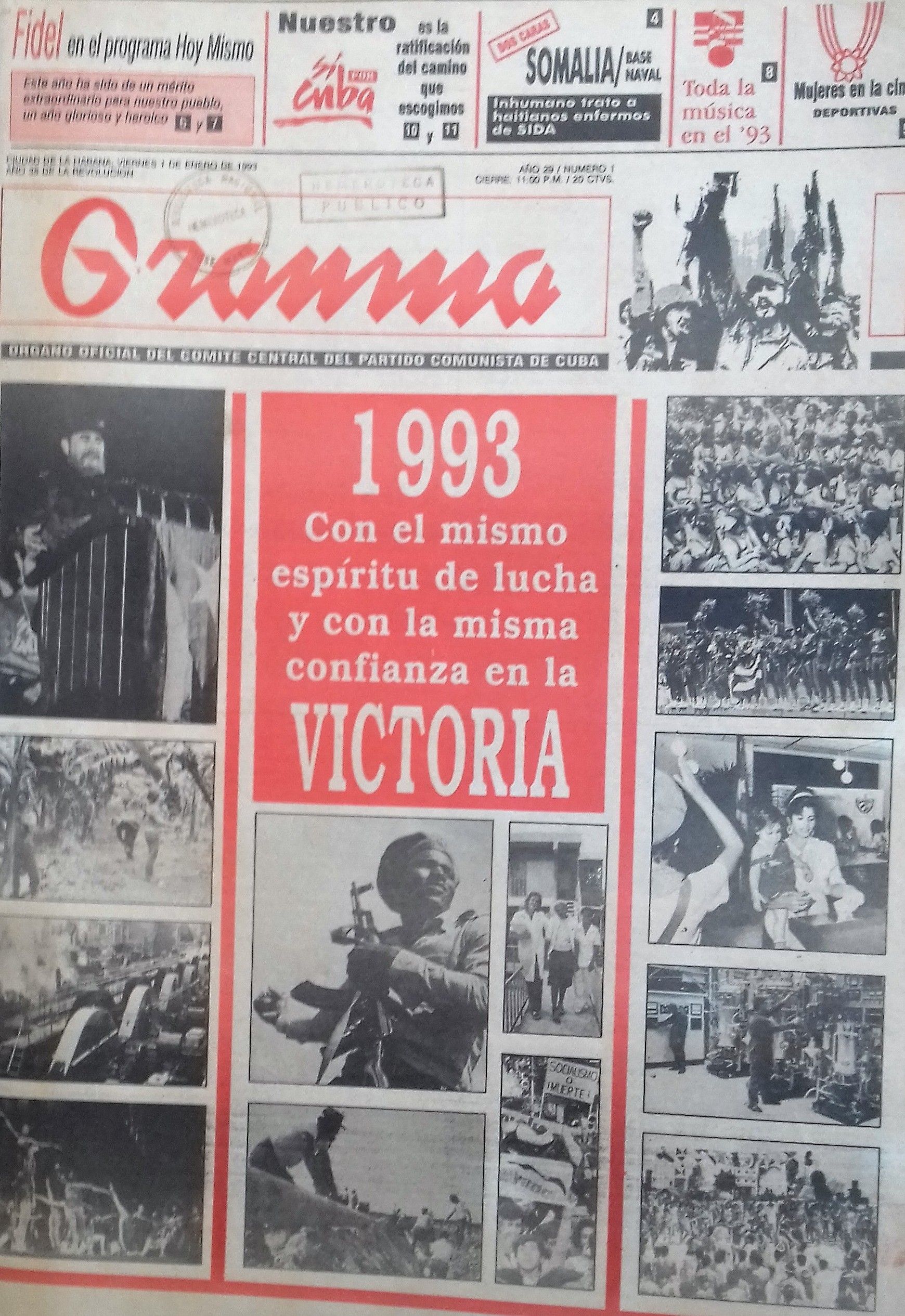

1993 – With the same fighting spirit and the same confidence in VICTORY.

The triumphalist view of the crisis we’re experiencing today is being interpreted as a means for the Government to subjugate Cubans with an ideal of resistance that is moving further and further away from their everyday experiences. Sacrifice, effort, and gratefulness to the Revolution are the values that are being pushed with a romanticization of shortages, painting a model citizen that needs to respond to the lack of basic products with discipline, while also serving a function that is very useful to the Government. They create a silent obedience for the system that gave us “everything”: “free” healthcare and education.

The moralizing power of these messages in the press, focusing on the “dignity” of the solution to hardship, is a distraction technique to sidestep more profound doubts. Instead of asking ourselves why we don’t have electricity, we adopted energy-saving practices for years, and; instead of asking ourselves where the meat ended up, they tried to substitute it with moringa, decrepit old chickens or innards.

But no, that’s not fair. Being poor isn’t OK. A State that doesn’t ensure dietary requirements, living conditions and quality services isn’t OK either. It doesn’t mean that the two men that joined two Lada cars together in the ‘90s to create the creole limousine don’t deserve all of our admiration and respect, or the person who thought of making some kind of detergent from sisal sap; but it also doesn’t mean we can forget what the source of what we’re living in Cuba today is.

Simplifying overcoming poverty to the personal story of a farmer who managed to produce on land with practically no supplies is a very comfortable story for the Government. Thus, they evade Responsibility because poverty is a structural problem that can’t be resolved with the initiative and ingenuity of a select few. This individual response, this applause for excessive effort distracts us from the problem at hand, it creates stereotypes about what our response should be to shortages and turns up this pressure on the rest of the population.

The good thing about having less shouldn’t be the norm or “morally correct”.

This article was translated into English from the original in Spanish.