Carlos Varela & the Freedom of a Woodcutter Without a Forest

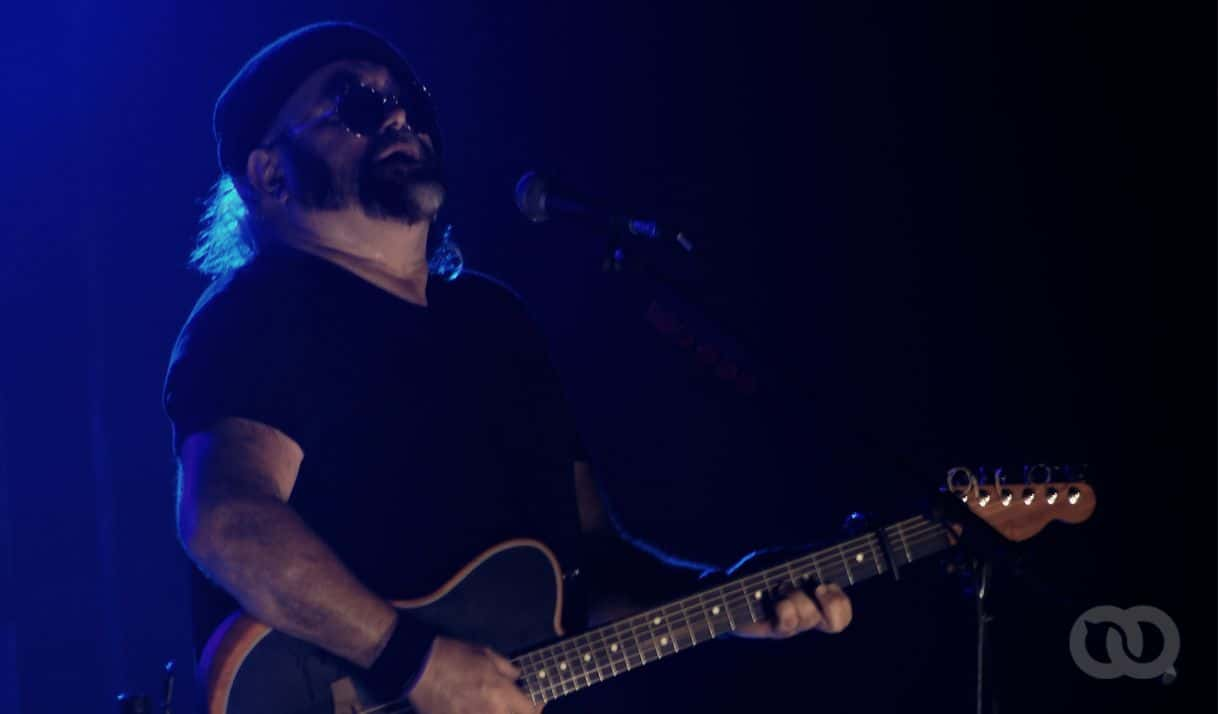

It’s the Havana World Music festival (May 19-21) at the Ciudad Deportiva. It’s my first Carlos Varela concert after so many years of waiting.

It’s about to turn midnight and you barely see anything just thirty meters away from the stage. Lights. Lots of drinks. Nearby, two girls take a selfie to upload to their Instagram stories. Two lovers kiss each other energetically to the beat of the music. A few people buy beer. A lot. Right behind my seat, three 30-year-olds, two girls and a guy, sing. The song Siete plays. They cry.

Those of us present could all tell a story of a family divided by politics, the story of a friend or a frustrated lover that is heading for the US’ southern border. A story of censorship, of intolerance or not very much hope. It’s Carlos Varela’s Cuba, my Cuba, the Cuba of many of those present, mostly young people.

Varela connects his music to many generations of Cubans, like very few artists know how to do. Maybe that’s because of the damn paradox that his generation’s problems are now our own. Maybe even worse. It’s the feeling of continuity. The reality of a country that is drifting in the ebb and flow of a political game where we are nothing more than pawns. The sentiment of generations who have suffered the consequences of intolerance on both sides of this cemetery that is the Florida Strait. Bitterness that has been sown.

Our inheritance. This burden that we are forced to carry on our shoulders, maybe even looking like we’re willing to carry it, but we don’t want to. At least we don’t. Much less so today.

His latest song, La feria de los tontos, triggers euphoria among those present. A girl moves her lips along to the unbridled chanting of those around her. She doesn’t know the words. She probably hasn’t ever listened to the music of a singer who has been singing about the same thing for over thirty years: an island and its demons.

“They made us all crazy, hoping for a dream, a broken dream!” They sing. She likes it. She smiles.

According to many people present, as the song played on, the police began to crowd around the platform. Minutes later, just a few meters from where we were standing, somebody shouted “libertad” (freedom). Hundreds followed. Most of the people in the Ciudad Deportiva did. Others clapped. The police remained stunned, shocked. Such a display of insubordination is out of their hands. A small act of rebellion. Cries in a mute city. Deeply spontaneous, temporarily free.

In today’s Cuba, libertad is a demonized word; perhaps the most prostituted and manipulated word. It’s a term that is able to provoke an almost obsessive and irrational fear in certain minds. How could they not be afraid of the cry of hundreds of young people who, at a concert, with alcohol running through their veins, are able to talk about freedom?

They didn’t see it coming. They were afraid. I’m sure. You could sense it. They didn’t cordon off the space between the steps and stage for no reason. Greater police presence outside when we left wasn’t for no reason either. Tension.

Probably for several years, most of the people present won’t be able to go to another Carlos Varela concert in Havana. Emigration is a cancer that spreads and eats away and bleeds the country dry. Cuba is a frail country that you only visit once a year to see your elderly parents. My friends also want to leave. They prefer “to be forgotten before being taken for a fool.” We’re another generation of woodcutters without a forest.

This article was translated into English from the original in Spanish.

Comments

We moderate comments on this site. If you want to know more details, read our Privacy Policy

Your email address will not be published. Mandatory fields are marked with *