Russia Extends Migration Deadline for Irregular Foreigners, But Doubts Persist Among Cubans

On April 28, 2025—just two days before the expiration of Decree 1126, which allows undocumented foreigners in Russia to legalize their status or leave the country without facing forced expulsion—President Vladimir Putin signed an amendment extending the deadline until September 10. The decision brought relief to many Cubans, but also a growing sense of uncertainty.

“They say there’s more time, but that doesn’t guarantee anything,” says Yaimé, a young Cuban woman who has lived in Moscow for two years and asked that her last name not be published. “I went to Sakharovo (the migration center) to get regularized—they took my fingerprints and everything—but as soon as I said I didn’t have a job contract or Russian family, they told me I’d be better off leaving the country. Just like that.”

Although the Kremlin has granted more time for migrants to get their status in order, experts warn that staying in the country still hinges on meeting strict requirements.

According to Cuban attorney Pedro Luis García, who runs the YouTube channel Moscú Express, the extension does not apply automatically to all migrants.

“Many people think that just because they’re here, they can stay until September. But that’s not how it works,” he explains. “The law applies to those who have a valid legal reason to remain in the country.”

Legalization or Voluntary Departure

García, who lives and works in Russia, emphasizes that this is not a blanket amnesty. “You need a legitimate reason to stay—like studying, working, or seeking asylum. Otherwise, you need to leave. And it’s better to do so voluntarily.”

He stresses that migrants without proper documentation must exit the country before the new deadline. Failing to do so could lead to deportation, especially for those with prior administrative violations, unpaid fines, or fraudulent paperwork.

He also underscores the importance of undergoing the official regularization process, which includes a medical exam, fingerprinting, and biometric data collection. This registration is not only crucial for those hoping to leave and return legally, but also for maintaining access to basic services like phone lines and banking.

“Without those documents, if your phone line or bank account gets blocked, you’re stuck. You won’t even be able to prove you’re in the country legally,” he warns.

García also cautions against visiting migration offices with irregular paperwork. His warning is not just hypothetical. Several Cubans have been detained for showing up with forged passport stamps or unpaid fines. On YouTube, a young man identified as Alain shared that he had managed to register and travel in and out of Russia without issues, but his friend wasn’t so lucky. “He got arrested over a fine he didn’t even remember he had,” Alain said.

A General Decree With Uneven Enforcement

Although the presidential decree is national in scope, its enforcement varies by region. In Moscow, the process appears relatively straightforward, according to García. But in other cities like Kazan, local officials remain unclear on how to implement the regulation.

That’s why caution remains the prevailing advice. “Every case is different. Ideally, people should legalize their status, leave the country voluntarily, and return later—if they can—with a new legal basis,” García recommends.

Amnesty or Revolving Door?

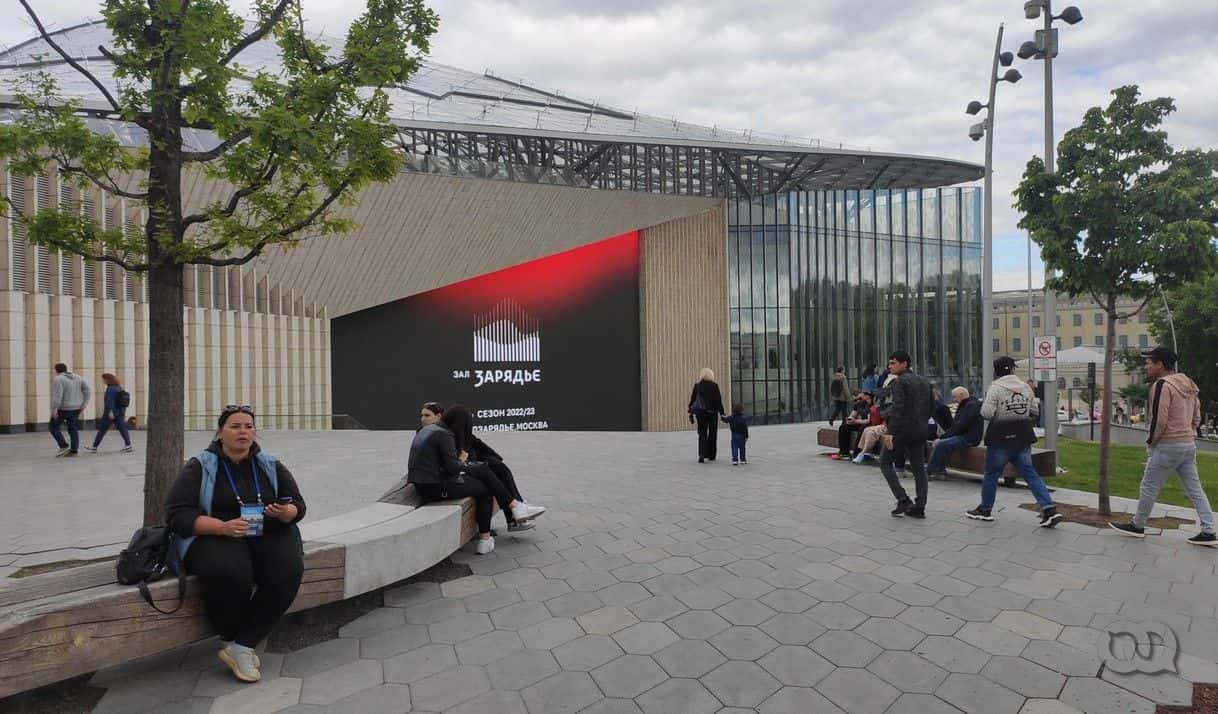

Russia has become a common destination for Cubans fleeing the island's economic crisis. Many arrive visa-free as tourists, but after their 90-day stay expires, they find themselves trapped in legal limbo.

In recent years, Russia’s immigration policies have grown stricter, often with little public notice.

While the extension until September 2025 may offer temporary relief to thousands of Cubans in Russia, it does not guarantee stability or long-term security. Without a more lenient immigration framework, many remain caught between the hope of staying and the fear of being expelled.

For those without a legal basis to remain, the most common advice is to leave voluntarily before the September deadline and try to return under different circumstances.

“I’m saving up to leave for another country, but there aren’t many options,” Yaimé says. “You can’t go to Serbia without a visa anymore, and getting into Europe after the war in Ukraine started is nearly impossible. There’s only Abkhazia or going back to Cuba—and everything costs money.”

“What Cuban here has the money for that? We live day to day,” she asks.

“But the worst part is being left without papers, without a bank account, without a phone line, in a country where everything is under control. What are we supposed to do? I don’t know—but it’s really hard,” she concludes.

It’s a familiar story: legal measures that inspire hope, only to leave more questions than answers. And once again, Cuba’s migrant community is left adrift, caught between the regulations of a foreign land and the necessity of leaving their own to survive.

Comments

We moderate comments on this site. If you want to know more details, read our Privacy Policy

Your email address will not be published. Mandatory fields are marked with *